10.30.2011 | 9:31 pm

You knew this was going to happen eventually, right?

I’ve been writing this blog for six and half years. During that time, I’ve written right around 1500 stories. Quite a few of those stories, alas, suck pretty bad.

Every so often, though, I’ve written a keeper. And just by the sheer force of odds, I was bound to eventually wind up with enough good stories to justify a printed collection of my good stuff.

Instead, though, I’ve decided to collect my absolute worst material, and make a book out of that.

Just kidding. I hope.

Anyway, check out the cover:

The title comes from the The Wit and Wisdom of Dr. Michael Lämmler, where he scolds me, “I hope your comedian mastermind this time around might actually get the point.”

Clearly, as of yet, I have not.

What’s Inside

Comedian Mastermind is the best stuff I wrote in the early years of my blog (as well as quite a few of my best stories for Cyclingnews.com and BikeRadar.com). It’s full of fake news, how-tos, epic (and not so epic) rides, the best cake in the world, the Assos ad teardown, Dr. Lämmler’s reply, my best Lance Armstrong and Tour de France stuff, and a bunch of other stuff that doesn’t fit into categories very well.

But it’s not simply the blog, bound up in book form. No indeed.

For one thing, every story has a new introduction, giving extra context — the story behind the stories.

For another thing, I’ve gone annotation-crazy on this book; I’m pretty sure there’s not a single page in the book that’s not loaded with ridiculous new observations in the footnotes section.

For yet another thing, Comedian Mastermind is a big, thick book: it’s 6″ x 9″, and about 350 pages. I promise, you are going to be all set for excellent bathroom reading material for months (approximately three months, in fact, provided you read one entry per day).

For still yet another thing, this book has been edited, which means — for the first time ever — you’ll get to see what my stories are like when they’re not a rushed first draft.

And to top it all off, it’s got a foreword from every single member of The Core Team. That’s five forewords. How many books give you that? Just one — this one — that’s how many.

Want to see what Comedian Mastermind looks like on the inside? Click on the sample page thumbnails below:

How Much Does Comedian Mastermind Cost?

The normal thing to do, when one writes a book, is to set a price. If people want the book, they come up with the money and they pay that price.

But I haven’t exactly done things the normal way, um, ever. So, how much this book costs is up to you. There are four different prices, to match four different groups:

- The standard “I like Fatty” price ($19.95): This is the normal price for a book like this. If you pay this, you’re saying, “I like what Fatty writes, would enjoy a compilation of his best work, and am fine with paying a normal-book’s-worth of money for it.”

- The “I Love Fatty” price ($29.95): If you’ve been reading my blog for a few years and have gotten more entertainment out of it than you get out of one normal-priced book, maybe you’d like to tip me an extra ten bucks. That would be awesome of you, and as a thank-you, I’ll autograph your copy of the book.

- The “I REALLY Love Fatty” price ($39.95): If you’ve been with me right from the beginning, or have started believing me when I say I’m a beloved, award-winning, internet celebrity, you can pay double the normal price, which is like tipping me twenty bucks. If you do this, I’ll not only autograph the book, I’ll write a note in the book that you specify (good if you’re giving it as a gift), or I’ll make up something a little bit over-the-top for you.

- The “I’m Nearly Broke” price ($9.95): If you’re hurting bad for money because you’re out of work or are a college student or you’ve donated all your discretionary money to the (seemingly thousands of) fundraisers I’ve done, get this version. I won’t make any money on copies I sell for this price, but that’s cool; I won’t lose any money on them either. And at some point, I think it might be valuable to me to be able to say, “I sold X thousand of my first self-published book” to someone, so you’re still doing something nice for me.

How Do You Order It, and When Will It Arrive?

Pre-order of Comedian Mastermind starts now, and ends November 10. At that point, I place the order, and then — once the books arrive at my house — start using child labor (specifically: a college student, two twins and a fifteen-year-old boy) to send your books out to you.

Your book will arrive on or before December 15 — in plenty of time for Christmas. Yep, that’s right, I’m urging you to give this book as a Christmas present. In fact, why don’t you give a copy of this book to every single person you know.

And that’s all there is to it. That’s not so bad, right?

What’s Next?

Comedian Mastermind is the first of a set of Best of FatCyclist.com books. How many will there be eventually? I don’t know; I guess it depends on how long I keep writing this blog. I’ve got two more outlined, so I hope to do at least that many.

I will tell you, though, that the next book in this set is going to be different than the others. While the other books in the series are just for fun, the second book will be titled Susan’s Battle, and will be a collection of all the stories I wrote about Susan’s fight with cancer, along with a lot of additional new stories, giving details that I didn’t give in the blog.

My hope is that the second book might be useful for people who are going through cancer, as well as for people who are taking care of a loved one with cancer..

Further, the second book will be a two-for-one deal. when you flip Susan’s Battle over, you’ll have the novel Susan was working on and nearly finished. For one thing, it’s a fun book and deserves to be read by more than just a few of Susan’s family members and friends. For another thing, I told Susan I’d get her book published.

I’ll be using the proceeds from both this first and second volume to fund my big dream: writing (and if necessary, publishing) The Cancer Caretaker’s Companion.

So, you remember when, last March, I wrote a post called “This is My Plan and This is What I Need“? Well, the plan is now in motion. And hopefully, I’ll be able to use the money and credibility the sale of a lot of books brings to get The Cancer Caretaker’s Companion the attention it needs.

Meanwhile, though: I’m proud of Comedian Mastermind. It’s a fun book, and all else aside I think you’ll get your money’s (however much it is) worth.

Even if the title does oversell itself just a touch.

Comments (65)

10.28.2011 | 7:43 am

A Note from Fatty: I love Joe’s perspective on suffering. I think I understand it, sometimes. Sometimes, in fact, I even have it. Sometimes.

I’ll be back Monday with (what I consider to be) a big announcement.

Have a great weekend!

Does anyone else have suffering games, or is that just me? When I’m riding a good threshold pace (about what one can sustain for an hour) math becomes fuzzy. This is a 78 mile race, we have gone 52 miles, how much longer?

Does anyone else have suffering games, or is that just me? When I’m riding a good threshold pace (about what one can sustain for an hour) math becomes fuzzy. This is a 78 mile race, we have gone 52 miles, how much longer?

This comes as a surprise to many who know me as an aerospace engineer.

Around my 5-min max I have trouble constructing sentences, and rather communicate using wheezes, grunts, and moans. A nice game for criteriums is what I like to call “The Name Game.” It’s easy, just spell your name. J-O-E. It’s what I ask myself when the race becomes truly difficult and I’m in danger of getting dropped. As long as I can spell my name I can go a little bit harder.

There have been times this was not possible.

Aspen to Crested Butte

I take issue to Fatty’s writing assignment title because it was “I’ve never suffered as badly…” I want to write about a time I suffered greatly. I decided not to write about a race, but rather my favorite ride ever.

My parents were visiting and I was riding from Denver to Durango, the best part being my mom was driving, so I never had to stop at gas stations or carry my own stuff. Not to mention the fact that point-to-point rides are the highest reverence to cyclists; the bicycle was, after all, designed to travel. I was on the third day of my trip and after watching the Tour stage and eating roughly 5 bowls of cereal, 3 bowls of oatmeal, 2 yogurts, and toast, I grabbed an English muffin for the ride and departed the hotel in Aspen bound for Crested Butte.

The first 30 miles were uneventful, some rolling hills and then false flat downhill to Carbondale. I felt unmotivated to ride and didn’t feel like I really want to be out at all, especially for this 107 mile journey.

After a hard left turn south I was riding false flat uphill for 20 miles along another river. This was a place I hadn’t been in CO before and the scenery just got better and better. When I hit the base of McClure Pass, a 3 mile, 1200 ft climb, I started drilling it, race pace. Now I was coming into this ride and loving it!

After eating a Powerbar (confession, I LOVE Powerbars) and grabbing two new bottles I continued the next 20 miles downhill into a valley where I made a left turn onto County Road 12.

The next 35 miles were the best of my life.

After I passed a few buildings, the road narrowed and turned to dirt. The first eight miles entailed being stared down by the 12,000 ft peaks in front of me, but little climbing to reach them. I was like a child on Christmas Eve, just waiting to start the climb!

Climbing is the best part of cycling. Packs shatter, there is no draft to hide behind, riders come unglued, and every emotion — from the excitement of the leaders’ battle, to the sympathy for the sprinters’ gruppetto — is released.

Hills are not in the way, hills are the way!

My wish came true abruptly as the road kicked up to 12% in the first series of switchbacks. The dirt road climbed 2300 ft over the next 10 miles and went through cattle ranches, dense trees, and openings with stunning views.

The road was narrow and windy, but the lack of traffic made it possible to utilize the entire road. For some reason it’s just fun to ride up the left hand gutter of the road. Any cars passing were yelling encouragement, honking, and giving thumbs up. The dirt was also the perfect consistency: soft, rocky, and bumpy enough to know for certain you are on dirt, but hard and smooth enough to stand occasionally and maintain control of the bike.

The suffering was real, but I was having so much fun I hardly noticed it.

A four mile downhill stretch had me drifting through corners and led to another 5 miles of climbing.

The last two miles were pavement, and they were terrible. The suffering was catching up. Without the distraction of riding on dirt, my mind wandered to, “Wow this is really steep” and, “Don’t cross the yellow line.” After gaining the summit I was a little confused how I had beaten my mom to this point, as she was driving.

There was no cell phone service so I bombed the seven mile descent into Crested Butte. It turns out my mom has a little fear of heights and was more than freaked out driving up that narrow mountain pass.

Our hotel was at the ski resort at Mt. Crested Butte, another two miles from town and the location of the finish for Stage 2 of the USA Pro Cycling Challenge. I rode out of town and charged onto the climb.

I was having the best ride of my life and was going to pretend I’m Levi attacking the final stretch, inspired by Phil Ligget’s voice in my head. I blew by another rider and was in full race mode. The hotel was in sight and I shifted into a higher gear to accelerate.

BOOM!

You know when you are watching the breakaway in the Tour and they start attacking each other near the end, and one guy seems to come to a complete stop as his bike turns 90 degrees to the side, and he throws his whole energy willing the bike to go forward and not to coast back down? That happened.

Cracked, blown, unglued, whatever you want to call it. This was not a bonk; a bonk is when one runs out of energy. I could have delivered a freight train of sugar to my legs and they would have said no more.

There were no stairs into the hotel lobby and I rolled into a very nice spa on my bicycle at an embarrassingly slow pace, cross-eyed and drooling. I tried to ask where to find food, but I think it came out as, “Where, store, here, town, food, fire truck, dirt road.”

After a few tries at a sentence my mom saved the day and showed up with a car full of food, drinks, and most importantly a hotel reservation.

It was my favorite suffering of all time.

About the Author: I’m a bike-racing rocket scientist who is not nearly as cool as that title sounds. I live and play in Colorado but I’m from the great state of NH. I’ve ridden coast to coast, rode a 7:32 Leadville 100, and rode the Tour of the Gila. Basically, I’m a bike nerd and my name is Joe.

Comments (16)

10.27.2011 | 7:33 am

A Note from Fatty: I’ve been quietly and secretly working on a big project recently. Monday I’ll announce it.

Another Note from Fatty: Today’s story, by Chris C, strikes kinda close to home, since I’ve been stuck in essentially the same place. It’s a great story of suffering. Enjoy!

Mid-March might be too early to ride Kokopelli’s Trail, but that’s exactly what my friends John and Kathleen and I set out to do. We are not novice riders: we’ve done distance, we’ve done mountains, and we’re all LT100 vets. Supporting us was our friend Doug (and his dad and son). He’s quick-thinking, even-tempered, and is himself an experienced enduro rider.

The whole group, left to right: Kathleen Porter, John Adamson, Doug Keiser, Chris Congdon, John Keiser, Brian Keiser

The third day was to be our toughest. 42 miles is not a long distance, but the terrain would be challenging. (Cowskin to Rock Castle) We’d start with a climb up a mesa, then down into and up out of two canyons … and then after lunch, a steady 18 mile climb to a point called Bull Draw, on top of a mesa at 8500 ft. At Bull Draw, our dirt road was to become paved for a nice six mile descent to camp.

The day began beautifully. The scenery was sensational as we dropped into slot canyons, riding rock trails and ledges. We made our lunch stop in the Fisher Valley. On this day, there was only one possible spot to bail out of the Kokopelli Trail, and this was it. It was 2:15 in the afternoon. It didn’t dawn on us that we had only covered half of our distance, but had already used more than half of our daylight. We had 18 miles of climbing ahead, but 18 miles is about the distance of one of my typical lunch-hour gravel road rides so why worry?

The road out of Fisher Valley was soft so it was hard to maintain momentum. Kathleen was feeling sluggish. Kat’s a strong rider, we all have our off days – unfortunately, this was one of hers. We were making only three miles an hour.

After setting up our campsite, Doug drove up to Bull Draw at the top of the mesa, and looked out in the direction from which we would come. As far as he could see, our route was covered in snow. We were heading into a mountain pass that hadn’t been traversed on anything other than a snowmobile since sometime last autumn. Doug drove the 30 or 40 miles back down the mesa, and then up the Fisher Valley to our bail-out spot, as he considered the snowfield impassible. Throughout the afternoon he’d occasionally try his cell phone, but there was no service in the valley.

On the trail, we continued climbing. I would ride a mile and then we’d stop to regroup. Kathleen was struggling. Sometimes John would ride with me and sometimes with Kat. Mostly he hung between us – keeping Kat in sight, but not piling on any more pressure. It was getting cooler as we climbed. We each had a light jacket in our packs, but that was it for extra clothing.

With about six miles to go in our climb we hit the first snowbank. It was small and we missed its monumental significance … that we were approaching the snowline, we still had six miles of climbing, and daylight was getting away from us.

The road became a sticky gumbo that collected on our tires and drivetrains and then our wheels wouldn’t go around anymore. We walked, slipping and sliding, pushing our bikes which had to weigh about 40lb with all the collected mud. After about an hour, we held a little council. Should we turn around? Ahead was 4 more miles of climbing – probably walking – and by this point turning around and going downhill in the mud also meant walking. We realized too late that we were in too deep.

We talked of splitting up, with me going ahead to tell Doug what was happening, but decided to stay together. I had a survival blanket in my pack, and if we had to spend the night on out on this mesa, we’d be warmer together. Also, we’d been seeing big kitty tracks. I didn’t want to be alone in the wilderness after dark. We’d occasionally try a cell phone call to Doug, but here in canyon country, we couldn’t connect. Kat fired off a text, thinking that Doug would receive it whenever he got back into coverage. John & I didn’t know what the text said. We pushed on. At nearly the last moment with enough daylight to read the map, we fixed our position with about 2.5 more miles of climbing to Bull Draw. We also had reached the snowfield.

During this time, Doug had made the round trip again from valley to mesa to valley to see if there was any sign of us. He was more than concerned. He didn’t consider the snowfield to be passable and yet we were not down in the valley, either. He concluded that we were in trouble, and that he was not going to be able to help us on his own.

We were struggling in the snowfield. I don’t want to over-dramatize our situation: we knew where we were, we had food, water and my survival blanket for shelter. But, you don’t have to read too many issues of Backpacker magazine to find a similar story with a grim ending. Our cause was not lost, but we had used up our allotment of bad decisions. We had to be hyper-alert for hypothermia and that precise moment when NOW is the time to stop and shelter-up for the night.

We had two miles to walk, in the dark, in the snow, in our spandex clothes and plastic shoes. Our mud-caked bikes were now accumulating ice as well. Every few steps they’d break through the crusty surface and sink to the hubs, and we’d have to heft them up again. It was totally exhausting.

Carrying the bike was too much for Kat, and she simply abandoned hers. She was stumbling a little and her teeth were chattering and I was scared for her, but it didn’t seem time to stop just yet. I walked ahead a little bit, trying to focus on the distant point that I hoped was Bull Draw. John kept encouraging both of us, and tried breaking a track for Kat to walk in. We walked single file, stopping often to rest, and in time, we tried Kat’s phone again.

Doug had decided to drive out of Fisher Valley until he had cell service, and then call for help. He had gone a few miles when his phone chimed. He stopped, read the text from Kat. “HELP” As he moved to dial 911 the phone rang in his hand. It was us.

We were able to tell Doug that we were in the snowfield with maybe a mile and a half to Bull Draw and he was able to tell us that the paved road down the other side was open and he would meet us there. At that point John and I also abandoned our bikes and we put our efforts into moving forward together.

John took the point and we walked like blind people, single file with our hands on the shoulders of the one in front. We could hear the wind roaring over our head, coming up from the other side of the mesa. We’d do about thirty steps, rest, thirty steps, rest. Our feet were freezing and the icy crust bloodied our shins.

And then … eventually … the snow wasn’t quite as deep. Snow became slush became mud and finally we were on blacktop. The icy wind made us have to shout at each other, but we were on pavement, walking downhill, holding hands: obviously the first cyclists to crest Bull Draw from Fisher Valley in the 2011 season. Ten minutes later we were in the truck.

Doug calls our cell connection a God thing, and I’m with him on that — what else could it be on a day that had offered no other communication? It would take a while for us to really warm up, and as tired as I was, I didn’t sleep very well that night. You can imagine that this has left us with a lot to talk about: bad decisions, fear, exhaustion. But we do these things for the experience — to have a story to tell.

And, I think it was at breakfast the next morning when John kind of smiled and said, “It was the best!”

About the Author: Chris Congdon is Media Coordinator at First United Methodist in Cedar Falls, Iowa. He loves road TTs and MTB XC racing. He says he’s not good at either, but has a ton of fun.

About the Author: Chris Congdon is Media Coordinator at First United Methodist in Cedar Falls, Iowa. He loves road TTs and MTB XC racing. He says he’s not good at either, but has a ton of fun.

Comments (23)

10.26.2011 | 7:14 am

A Note from Fatty: Today’s story comes from Michael S, who is very mysterious. Which is to say, he didn’t send in a bio. A great story of suffering, though. Enjoy!

My list of things that went wrong that day seems endless. I’d gotten four hours of sleep the night before, special thanks to a fussy infant, and at 7 a.m., my wife and I had a nasty little argument we would later refer to as the “worst fight of our marriage.” But somehow our little family of four still found itself on the highway to Jackson Hole, Wyo., for the bike race I’d been planning that day, the Rendezvous Hill Climb.

Then, while I was warming up minutes before the start, I hit some loose gravel and went over the handlebars, landing on my knee and hip. I was bloodied, bruised and starved–I guess a bowl of Marshmallow Mateys four hours beforehand wasn’t the best nutrition strategy. I was almost hungry enough to actually pay for resort food.

The locals in Jackson Hole are all a bunch of semi-pro studs, and every time I race there, I feel a bit like a 5-year-old among Greek deities. The Rendezvous Hill Climb had been on my race wishlist for years, but I’d never done it before. I’d just read that it climbed 7.2 miles and 4,139 feet from the ski resort to the top of their aerial tram. But it wasn’t until I was standing there being dwarfed by this gargantuan mountain that I realized that this might be a little beyond my abilities. I nearly peed my chamois just looking at it.

Keeping with my Greek tragedy theme, I’d been a little hubristic going into this. Most of my “training” consisted of pulling my kids in a trailer for 6 miles around our rural neighborhood. Since I knew I wasn’t in great shape, I figured I’d take it really easy, so I showed up with sandals and platform pedals rather than my regular clipless pedals. I’d even worn baggy shorts. Dumb. Standing on the start line, I felt a sharp twinge of insecurity.

“Is anyone else doing this tourist-style?” I asked the 11 svelte, spandex-clad racers lined up next to me. One guy put his hand up and smiled. I felt better. Then the race organizers told us to go. And just like that, we hurtled ourselves at this towering giant like a bunch of stubborn Lilliputians.

Once we got going, it wasn’t so terrible–just rolling and rocky. I actually motored on ahead of some of the folks on the really nice bikes at the first rise. Things got a little steep, so I tried to shift into my granny gear, and, of course, my chain dropped completely off the chainring. “No problem,” I told myself, “I’ll just fix this and catch up.” But after I remounted and turned the next corner, something else happened that guaranteed I wouldn’t be catching up, and it wasn’t a mechanical.

It was a 25-percent gradient that lasted at least a quarter of a mile.

Now, I don’t know if you’re familiar with 25-percent gradients, but I certainly wasn’t. “Is it really possible to ride up something this steep?” I thought as I dismounted and started pushing my bike up the slope. Obviously it was, since the other racers seemed to be managing it. I swung my leg back over the saddle as the pitch eased slightly, and I realized I was in for a long climb.

All the racers had left me behind except one lone straggler. I figured he must be sick or maimed or something. I rode up next to him and asked, “So, is this just a training ride for you?” His response: “I’ve only ridden my bike once this summer. I’m taking it slow because I know what’s up ahead.”

Comforting.

As the valley sunk beneath us, I actually managed to distance myself from him. When I looked down, the resort seemed like a distant ant farm.

The honest-to-goodness truth is that there isn’t much to tell you about the next 90 minutes. The fireroad coiled up through 7,000, then 8,000, then 9,000 and finally 10,000 feet above sea level. There was no shade, and the sun seemed to bear down hotter and hotter as the air became thinner and thinner. The road reflected the heat right into my face, and the mountain wasn’t shy about doling out punishment. I’d spin my granny gear until the gradient became too steep to handle (which seemed to happen pretty often), then hike, ride, hike, ride, hike, rinse and repeat-for well over an hour and a half.

Other than an occasional silhouette, I hardly saw anybody–not even a yodeling Swiss hiker. I was out there alone, and I soon found myself utterly demolished, completely out of water or nutrition, and becoming just a teensy bit delirious.

So, naturally, I started talking to myself like a schizophrenic. “I owe my wife an apology,” I told myself. “I just want to get this over with so I can hug my girls and get a burger.”

My introspective conversation was interrupted when I came across a guy sitting on a rock snapping photos with a large telephoto lens and looking a bit like a leprechaun guarding a pot of gold. He was a photographer from the local newspaper, it turned out, and he told me I didn’t have much farther to go. I thanked him, pedaled some more, hiked, rounded one more switchback, hiked again, then saw the tram dock in the distance–and took a gasp of relief!

As I got closer, I also saw three familiar apparitions, one of which had pigtails. I knew I wouldn’t have been the first guy on this planet to see blonde, female mirages, but these ones looked an awful lot like my family. “Great,” I thought. “Now I’m hallucinating.”

Then one of them yelled, “Dad!” and ran toward me. Then she tripped and fell on her face in the dirt. Luckily, instead of crying, she stood up and smiled. So I smiled back (or grimaced–I’m not sure which). “I love you, sweetie,” I told her in a sort of Sahara-desert-survivor tone. Then I churned the remaining 40 feet to the finish line. I finally released my handlebar death grip, elated just to be done. I could feel every inch of that mountain in my legs, and I could hardly walk to the tram dock.

Later, at the paltry awards ceremony, my kids-the only kids there-wouldn’t stop screaming at each other. My hip was still sore from my crash, and my wife was still mad at me (perhaps more than before). To top it off, days later, a photo of me would appear in the local newspaper next to some race results that would incorrectly and humiliatingly list me as dead last.

The next year, that race would cease to exist.

But on the upside, I’d managed to survive my own Greek tragedy, without marrying my mom. And at the end of the day, that’s a success, no matter how you toss it.

Comments (21)

10.24.2011 | 6:58 pm

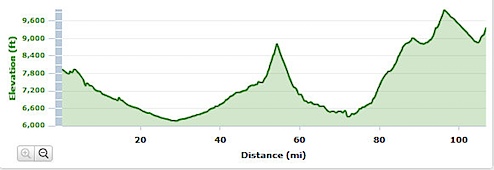

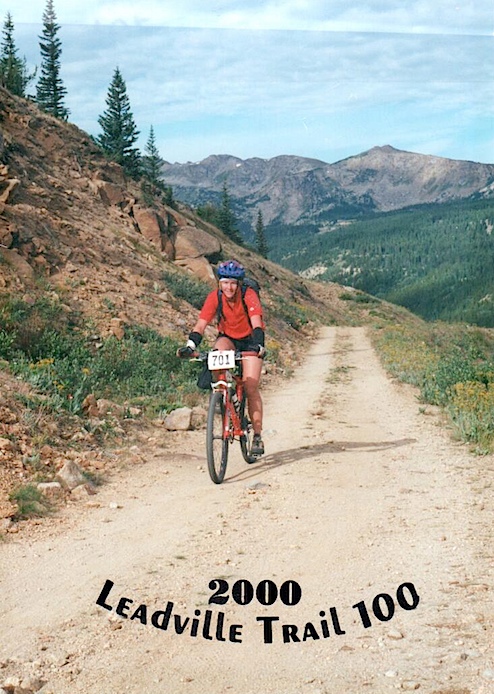

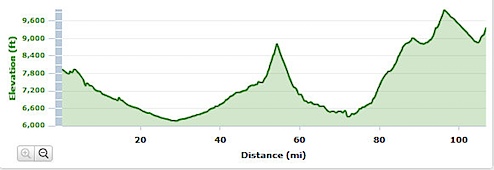

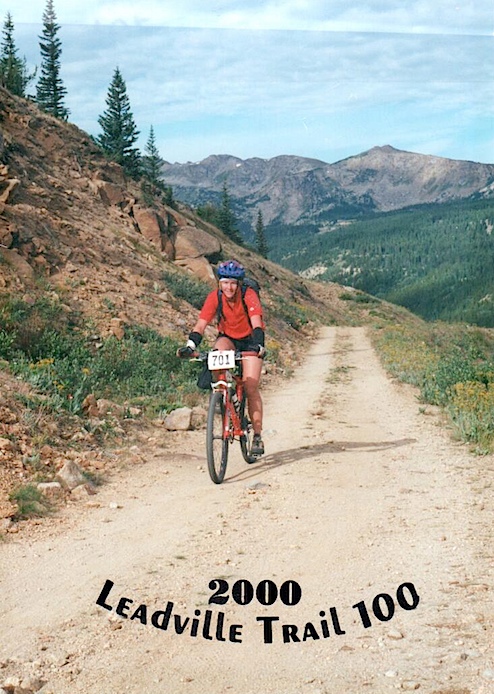

A Note from Fatty: Today’s “I’ve Never Suffered So Much” story comes from The Hammer, from the time she raced the Leadville 100 for the first time…back in 2000. Enjoy!

Sometimes the times in our life that we suffer the most, we end up growing the most too. The most suffering I have ever done on a bike occurred back in 2000. During that suffering, I dug deep into my soul and found out what Lisa is really made of. In fact, I would say that was a turning point, a defining point in my life. And it occurred on my bike. I guess maybe that is why I have come to love my bike so much–it truly helped me figure out who I am and how strong I can be.

It was the first part of August 2000. My brother, Scott, and I had been training all summer long for the Leadville 100 mountain bike race. Nine months earlier, my neighbor, Elden Nelson, had persuaded me and I, in turn, persuaded my brother that we should attempt the Leadville100 mountain bike race.

Elden explained how challenging and how fun it was. His stories hooked me and I signed up. My brother and I rode every chance we got. We only had mountain bikes, so we rode our mountain bikes every where-on the road and trails. We rode Elden’s Gauntlet -(80 miles and 8000ft) on our mountain bikes! It is tough enough now on my road bike; I do not know how I did it on a mountain bike! Let’s just say-you move a lot slower on a mountian bike. (It took about 3 hours longer on my mountain bike, turning a 6 hour ride into a 9 hour ride!)

During these training rides my brother and I found that we were quite comparable in biking abilities, and enjoyed riding together. Our relationship grew as well, my brother truly became my best friend.

Up until the time I left for Leadville, I could have chosen any number of my training rides and said they were the “most suffering” I had done on my bike. Every training ride seemed to push me past my perceived limit of what I thought I could ride.

As we packed the truck with our bikes and gears that August mornng we were ready. We had put in the mileage and we thought we were ready for the challenge.

First Blood

As we were driving up Spanish Fork Canyon (voted one of the most deadly stretches of road in the US), on our way to Leadville, we were all happily chatting about the upcoming race. My husband was driving the truck, I was sitting in the passenger seat, and Scott was sitting directly behind me. In one brief moment, I looked up and out the front window and saw something flying towards us.

My mind didn’t comprehend what was coming towards me; I just knew it was coming fast and I braced myself for impact.

And then the windshield exploded. But nothing ever hit me!

I was screaming and confused. My husband was yelling something about them not knowing they even hit us! I turned to my brother in the back seat and frantically asked if he had been hit…by what I didn’t know!

His head was rolling around on his neck, his glasses were knocked off, and his mouth was bleeding. As my husband was pulling over, I found out what had hit Scott. A piece of metal, 3 inches thick and 18″ x 4″ long had come flying through the windshield and had hit Scott in the face.

Thank heavens, the piece of metal hit the hood before it came through the windshield, knocking it off its missile-like track or it would have decapitated my brother.

Instead it struck my brother in the face, breaking his nose and knocking his front teeth loose, as well as cutting up his face. A semi-truck that was passing us must have kicked up this piece of scrap metal and sent it flying through our windshield.

After an ambulance ride, an ER visit, a bunch of stitches in the mouth and face, a visit to a ENT who said Scott nose was broken (but not displaced), and a visit to our dentist, we made our way back home.

Bruised and broken, Scott was still determined to do this race.

Our dentist got to work making scott a brace to keep his loose teeth in place, and the next day we were on our way to Leadville…again! My brother was (and is) amazing! His mouth and nose were so swollen he could hardly breath, but he didn’t complain! He was there to race and tackle the beast known as the Leadville100.

Maybe someone was trying to tell us something. Maybe we shouldn’t go to Leadville and race. Maybe we should wait and try again another year.

Well, whoever was talking, we weren’t listening!

The Race

After a rainy week, Saturday morning dawned with a few clouds over head. Scott and I lined up together. He still wasn’t complaining, and said he was able to breathe through his nose. Thank heavens he didn’t feel like he looked! He looked like he had been through a meat grinder and his nose was huge.

We started the St Kevins climb together, but we quickly lost each other. We had decided that this was an individual race. If we were able to ride with each other,great, but if not, we would tackle it solo.

As we left the dirt and started to descend on the paved road, Scott went sailing by me, yelling words of encouragement. Then, not two minutes later, my back tire started making a funny noise, and my bike started to shimmy. I slowed down and — to my horror — saw I had a flat tire! I pulled over, pulled out a tube and proceeded to change my tire.

Now, I need to stop telling this story to interject something here. Men, don’t rescue your wives and girl friends every time they need help. For example, if they have a flat tire while riding their bike, let them change it! Don’t help, dont step in half way through because they are going too slow and finish it for them. Let them change it all by themselves, from start to finish!

Needless to say, I had never changed a tire by myself prior to this. Granted, I knew the concept, I knew what I should do and how to do it, just never done it by myself!

So…forty five minutes later, after everyone in the whole bike race had passed me by (I’m not exaggerating, either), I put my bike tire back on and started down the hill, only to find that the tire wasn’t spinning right and was making a thumping sound! I was frustrated and so very angry at myself for being so dumb.

As I turned off the pavement and started up the single track, there was a man there directing traffic. I showed him my wheel and he laughed (it is so funny–haha). He explained to me that I didn’t have the wheel seated correctly. He put the wheel on right and I was off.

As I started up the single track, I passed a very old man pushing his bike! Yeah! I was no longer the last person in the race.

The official Leadville 100 photo makes it look like I’m the last, but by now there was actually one person behind me. Or maybe three.

As I rode I continued to put myself down, telling myself how stupid I was that I didn’t know how to change a tire! How stupid I was to be the last person in the race! I eventually rolled into the first aid station. I was lucky they weren’t pulling people off the course yet for being too slow!

Eventually I made it to Twin Lakes. My husband was there–wondering what had happened to me! He said Scott had stuck around the aid station for thirty minutes, waiting for me. He was worried about me–him with his broken nose and face! Scott had left about 10 minutes earlier, I might be able to catch him!

Thus far, I would say I had suffered more mental anguish than physical pain. How could I be some dumb? My success in the Leadville 100 was about to be ruined by my inability to change a tire, not by my physical prowess!

Then, as I rolled up Columbine, my spirits started to lift. I started seeing people and passing them. The adrenaline was coursing through my veins and I was feeling invincible.

The death march to the top was pretty tortuous, but I was no longer alone, I was surrounded by other riders now. I rolled into the 50-mile aid station and turn around point in six hours and to my amazement and surprise caught up with Scott! I was ecstatic!

Maybe, just maybe I could finish this thing in twelve hours!

Scott and I descended Columbine together and rolled in to the Twin Lakes aid station together. We grabbed our windbreakers (I didn’t have a rain coat) and headed out.

And that is when the story turns ugly.

Not five minutes later, the heavens opened up and the rain began to pour. The next 20 miles has become a blur of rain and cold. As we started up the dreaded power line climb, I pulled ahead of Scott and thought I had lost him for good.

As we pushed our bikes up the power line climb, the lightning was flashing overhead and the power lines were humming loudly. The words of warning about lightning from the pre race meeting were ringing in my ears, but I thought “to heck with them! I might just make the 12 hour mark–a little bit of lightning is not going to stop me!”

There was a steady flow of walkers ascending power line who must have shared the same sentiment as me. While I was climbing, I guess I didn’t realize how cold I was, but the realization of the cold hit me as I began the descent. I couldn’t shift with my fingers, I had to use the palm of my hand. Braking was non-existent. The grime from the muddy dirt had worn my brake pads and all my cables had stretched out.

If I couldn’t change a tire on my bike, I certainly knew nothing about tightening brake cables.

As I came out of the single track section onto the paved climb, I had to have a volunteer tie my shoe. My hands were so frozen I couldn’t do that myself!

The same volunteer asked if I wanted a garbage bag to wear. In my frozen, brain-dead state, I declined. I also declined food.

I was entering the worst bonk of my entire life. Up to this point in the race I think I had consumed about 10 power gels. Not even close to enough nourishment for a twelve-hour endurance ride in the freezing rain.

I do not know how I had the strength to make it up the paved road, but somehow I summited and thought I had made it, and it was all downhill to the finish line. I knew it would be close to the 12 hour mark, but I was hopeful.

But I was wrong, it wasn’t all downhill. Someone kept throwing in these damn uphill sections!

Finally , I descended St Kevins and my bike computer said 98 miles. I was almost there! But where was the uphill Boulevard that everyone talks about? I was so cold, my brain seemed to have stopped working.

Now my bike computer said 100 miles, but I saw no finish line. I just kept pedaling. I could no longer hold my head up. My neck muscles were gone. My head had fallen forward and was resting on my chest. I could only see the front tire and dirt road.

I think I must have been going five miles per hour. I had been out in the pouring rain for more than four hours.

And I just kept pedaling.

Finally the dirt road turned to pavement. I was getting closer. I had to use all my might to throw my head up and look forward. Eventually I saw the finish line! What was the time? I really didn’t know or care. I just wanted the misery to end.

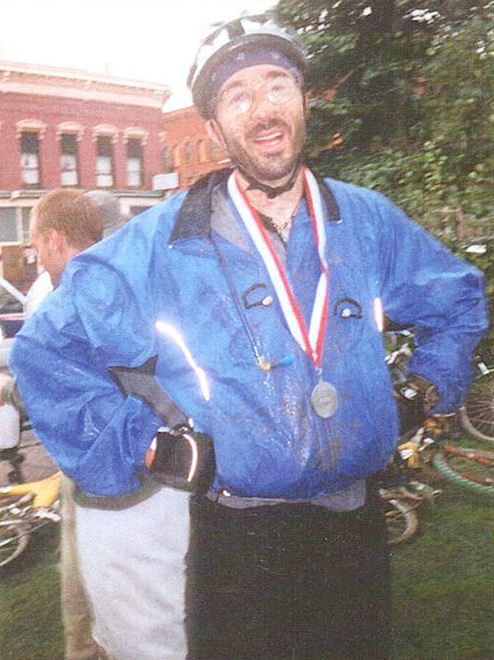

As I crossed the finish line, my head was hanging (I really couldn’t lift it up), I stopped the bike and just stood there.

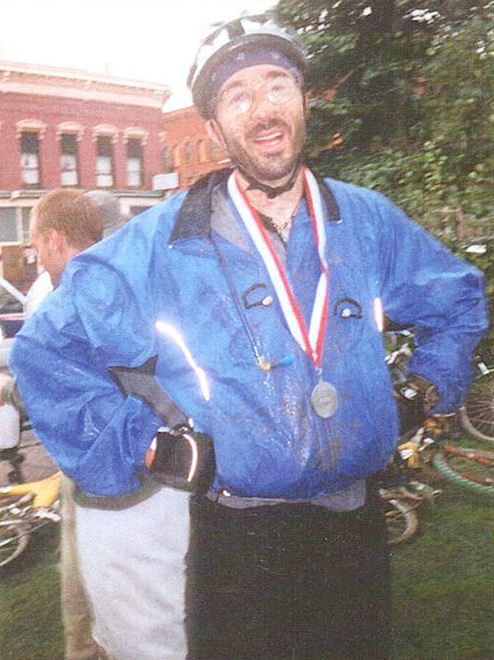

Everyone was telling me to get off and get to the medical tent, but I couldn’t. I couldn’t get off my bike. I had no strength to even lift my leg over the bike. Someone finally laid the bike down [A Note from Fatty: That was me.] and I stepped over it.

They got me to the medical tent, stripped off my wet clothes and put me in a sleeping bag. I was on the verge of passing out. If I closed my eyes I thought I would pass out. Everything was swimming and I was so dizzy. As a nurse, I would have loved to know what my body temperature was.

I finally started shivering. Up until this point I hadn’t shivered, I think I was shutting down. When the shivers started, they were violent!

After more than an hour of sitting in an ambulance with the heat blazing, I finally started to warm up.

So had it all been worth it, did I make the 12 hour mark? And what had happened to Scott, did he finish? Was he as cold as me?

Yes, I finished in 11 hrs 55 min and 30 seconds. I wasn’t even the “last ass over the pass,” there were seven people who finished behind me. And one of them was Scott!

In fact, he finished five seconds behind me! I didn’t know he was behind me and he didn’t know I was ahead of him.

He was cold, but not as cold as me. More importantly, he had taken the time to eat. I think if I had taken in a few more gels, my body would have reacted better to the cold.

I definitely learned a few lessons from “my most miserable day on a bike” about racing and about life that day! I learned a few important things about nutrition and clothing choice when racing in high altitudes.

More importantly, though, I learned that when faced with a challenge, I can push myself harder and farther than I thought I could. And also, when you’re faced with a challenge, sometimes it’s better to stop and take a breather: reassess the situation, utilize the help around you and then continue on.

I learned I can push through just about any physical challenge thrown at me while on a bike, but I need to learn to accept the aid along the way.

In the years that followed my first Leadville100, I was faced with many hardships; many wondered how I kept myself together. I think it was because I learned who I was and what I can handle on a rainy mountainside in Leadville, CO.

Comments (37)

« Previous Entries Next Page »