09.30.2013 | 8:23 am

A Note from Fatty: Looking for earlier installments to this series? Here you go:

- Part I: The Things that Hurt

- Part II: Meet Your Competitors

- Part III: Team Fatty Cannot Seem to Catch a Break

- Part IV: Support from a Unicorn

- Part V: Life as a Domestique

We had just finished the first hundred miles of a 423-mile ride. So, not quite a quarter of the way done. Still, I had decided that anytime I hit a hundred mile mark, I was going to celebrate.

“We’re 25% done!” I shouted to The Hammer. “We’ve got a good start!”

She agreed, nodding her head. I wondered if she was thinking about the strangeness of what I had just said in the same way I was: calling a 100-mile ride “a good start.”

But in our heads, that’s the way it was. Normally, by the time we reach the 100-mile mark, our bodies and minds are ready to get off the bike. But we had thought about the distance and the time for this race long enough, and had told ourselves that getting to Nephi — kind of our outer-limit-distance for training rides — was where the ride really began often enough, that I didn’t expect to feel tired at this point.

And, amazingly, I wasn’t tired. I was just fine. So much of endurance racing is a mental game.

Oh No, Not Again

Within five miles of swapping out to our road bikes in Nephi, I could tell something was wrong.

My bike felt squishy. Sloppy. It’s a very distinct feeling.

It felt…the way a bike feels when a tire is slowly going flat.

“Maybe it’s all in my head,” I said to myself, knowing that this is not something that is ever all in my head.

“Is my rear tire low?” I called back to The Hammer.

“I don’t know. Maybe?” she yelled up to me. Which was less than confidence-inspiring.

So I pulled over, twisted around, and pressed my thumb down on my rear tire.

Yup. Going flat.

At which point I began softly weeping.

A Quick Change

I barely had time to climb off my bike before Scott and Kerry pulled up behind us. “Well, at least I can use the floor pump to inflate the tire,” was pretty much all I thought.

The Hammer, though, had an idea that would get us on the road sooner. “Have them change the tire while you just switch over to your Shiv for the time being.”

“Hm,” I replied, looking for a way to put my objection delicately.

“What’s the problem?” The Hammer asked.

“I don’t think Scott or Kerry, you know, ride,” I said. “Do either of them know how to change a road tire?”

“Scott used to mountain bike; he knows how to change a tire,” The Hammer assured me.

“You’re OK to change a tire?” I asked Scott. “You’ll need to be sure to use one of the tubes with an 80mm stem, OK?”

“Sure,” Scott said.

“OK, let’s do it,” I said.

I told The Hammer to go on without me; I’d catch her as soon as my bike was unloaded. Within a couple minutes, I had the Shiv off the rack and was on my way.

A “Quick” Change

With The Hammer a couple minutes ahead of me, I was breaking one of the main rules we had set for ourselves at the beginning of this race: we stay together.

Now, in order to catch up with her, I broke another of our primary rules: stay out of the red zone. I stood up and went as hard as I could, figuring that once I caught up, I could back off for a few minutes and recover.

And that worked out just fine. Within ten minutes, I had caught up with The Hammer. “Let me draft behind you for a few minutes, OK?” I said.

Then, just about the time my breath was back to normal and I was ready to start taking turns at pulling again, Scott and Kerry drove past us, pulled off the side of the road, and unloaded my road bike.

“This will take less than a minute,” I said. “Just keep going and I’ll catch you after I hop off this bike and onto my road bike.”

So The Hammer kept going while I slowed down, dismounted, grabbed my road bike, shouted my thanks, and got riding again.

And then immediately stopped.

Something was seriously wrong with my bike. I could barely turn the cranks. I climbed off, lifted the rear wheel off the ground, and gave it a quick spin.

The wheel did not budge.

As I climbed off my bike, I noted that The Hammer was disappearing from sight; she didn’t realize I was having bike trouble.

Should I get back on my TT bike? Or fix my road bike? I decided to fix my road bike; this was a climbing section; I’d be standing often. I wanted my Tarmac.

So I looked down and noticed two problems I was going to need to address:

- One of the brake pads was halfway out of its track.

- The brake calipers were tweaked hard to port.

I couldn’t help but ask Scott and Kerry, “What happened here?”

“We had some trouble getting the wheel back in place once we changed the tire,” Kerry told me.

“Don’t worry about it,” I said. Honestly, I just didn’t want to hear any more.

“So, could you go get my hex wrenches out of the blue bin in the back of my truck?”

I took the rear wheel off, got the brake pad back in place, and then re-centered and tightened the brake calipers. That pretty much takes me to the outer limits of my mechanic skills, so I was glad it wasn’t any trickier to fix than that.

“OK, I’m off again. See you soon!” I hollered.

I didn’t know how right I was.

I Love My Tarmac

Look. The Shiv is a fantastic bike. It’s amazing, frankly, at doing what it does best: go really fast on straight, flat roads. I mean, The Hammer and I had just knocked out seventy miles with hardly any effort at all on those bikes.

That said, I was so happy to be back on my Tarmac. I love that bike. When I’m on it, I just feel great. I can get in the drops and descend like a hawk. I can get on the hoods and ride forever. I can stand and climb forever.

It was the “stand and climb forever” part that came in handy now, cuz I figured The Hammer was at least eight or ten minutes ahead of me. “Miles,” I thought to myself. “I have miles to make up.”

And so I stood up and rode. Hard. Riding like I was going to be out for another hour or so, instead of for another twenty or so. Knowing that what I was doing was stupid strategy, but not really caring.

Because I love the way I can go on the Tarmac.

And sometimes love makes you do stupid things.

So Close

For twenty, I pushed myself. Just rode myself into a hole. And then I could see her. I had The Hammer in sight. “Another three minutes,” I thought to myself. “Three minutes and I’ve got her. And then I can draft off her for ten minutes or so, and everything will be great.”

And that’s when my bike started feeling squishy. You know, sloppy.

It’s a very distinct feeling.

I pulled over, watching The Hammer disappear again.

Which is where we’ll pick up tomorrow.

Comments (41)

09.27.2013 | 10:19 am

A Note from Fatty: This is Part V of the Salt to Saint Race Report. You can (and should) read previous installments first. You can find them here:

Technically, it’s possible to be geekier than The Hammer and I were being. For example, neither of us were wearing our time trial helmets. Nor were we wearing skin suits (though we did have them in our respective clothing bags, just in case).

That said, we were on Specialized Shivs — outfitted nearly identically with Shimano Dura Ace C50 wheels and Shimano Di2 Ultegra drivetrains. The Hammer was riding no more than three inches behind me.

So yeah. We were kinda geeky.

And also: we were hauling ass.

Reunited with our crew (and all our stuff), as well as the switchover to our TT bikes just in time to begin a seventy-mile flat section�, The Hammer and I were ready to put all the strangeness of the first couple hours of this race behind us and go.

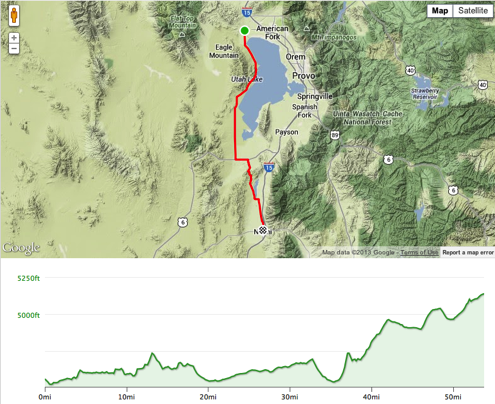

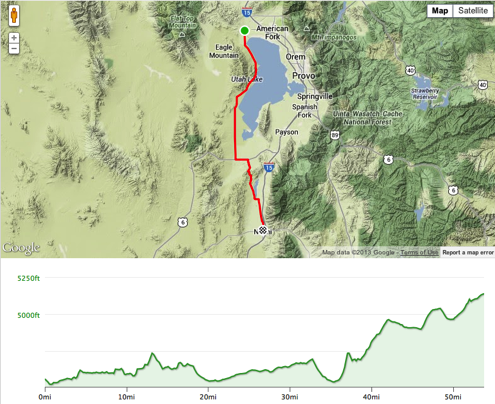

The section going from the west side of Utah Lake to Nephi is maybe the flattest, straightest fifty miles of the Salt to Saint race.

We wanted to take advantage of it. With The Hammer in tow, I got nice and low on my aero bars, moved forward on my saddle, and inched my speed up to around 23mph. I was still in my “go all day” zone, but only because we were nice and low on our Shivs.

Jake and Jason, Part IV

The Hammer and I started reeling in all the people who had left us behind during our first couple of troubled hours of the race. We’d say “Hi” or “Good luck” as we went by, but we didn’t really care about whether we were faster than they were, or whether they were faster than us. They weren’t our competition.

Then we caught up with Jake and Jason, the two guys we’d briefly ridden with at three other points in the race.

“Back in the saddle again?” asked Jake.

“Hey, nice bikes,” said Jason.

“Hop on the train!” I yelled over my shoulder. It was time to repay their generosity of earlier in the race.

Three minutes (or so) later, I yelled back over my shoulder, “Are we all together?”

“They never latched on,” The Hammer yelled back.

“Oh. Ugh. Well, they’ll catch and pass us later, I guess,” I said. “But for now, you know what?”

“What?”

“We are the lead solo riders in the 2013 Salt to Saint.”

Domestique

There’s nothing like the blur of a front wheel and a white line perpetually sliding by to hypnotize you. I disappeared into my own thoughts, my mind quiet, my legs doing what I’ve trained them to do for the past twenty or so years. The Hammer rode close behind me, just like we had planned. It was my job to get her to the second half of the race feeling like she could do another 200 miles.

And I was loving my job.

I thought a little bit about how sometimes, when I watch big races like the Tour de France, I feel bad for the domestiques — the guys who have the job of protecting and taking care of their race leader. I think, “It must suck for them, to have the job of helping someone else win.”

But while riding the Salt to Saint, with my primary objective being to ensure that The Hammer be the first woman to ever solo that 423 race, I finally understood: being a domestique is wonderful. You’re taking care of someone you care about; you’re an integral and necessary part of the win. Being a domestique in a true team, I realized, is something to take an enormous amount of pride in.

We rolled along, enjoying the speed, the cool day, the mild-to-nonexistent wind. Scott and Kerry, The Hammer’s two brothers, had taken over crewing duties and were making sure we had everything we needed. Which, more often than not, was either a Red Bull or a Coke. The Hammer and I are officially addicted.

Tweeter and the Monkey Man

Everything was going perfectly.

And then tragedy struck.

OK, maybe calling this a “tragedy” is overstating my case, though only by a little. I’ll tell you what happened, and then you can decide how bad it was:

The song, “Tweeter and The Monkey Man” by The Traveling Wilburys got stuck in my head.

And it would remain there for the next twenty hours, with the occasional substitution of “The Wilbury Twist.”

Yes, I own both of the Traveling Wilbury albums. Yes, I like both of them. But I haven’t listened to either of them in at least two years. So what were they doing there, replaying over and over in my mind? Maybe they just happened to match my cadence or breathing or something.

May I Take Your Order?

We got to and through Elberta, then into Goshen Canyon — one of the most scenic parts of the early section of the race. We were headed toward Nephi, which was important because we’d have completed the first 100 miles of the race. A quarter done! That’s significant, and I planned to announce it with great fanfare. Which is to say, I intended to say, “Hey we just hit 100 miles!”

But that was still more than an hour away. Right now I just took a Coke from our crew.

The Hammer, on the other hand, had more complicated instructions.

“We want you to drive ahead now to the Wendy’s in Nephi,” she said. “We’ll meet you there. Have our road bikes off and ready to go with a full bottle in each of them.”

Scott and Kerry said they’d take care of it.

“But more importantly,” The Hammer said, “I want you to go to Wendy’s and get me a four-piece chicken nuggets and a small vanilla Frosty.”

I started laughing. The idea of eating fast food in the middle of a race sounded completely ridiculous.

But about five minutes later — after Scott and Kerry had taken off ahead of us — I started thinking, Hm. That actually sounds really good.

“Honey?” I asked, “Can I have a bite or two of the Frosty?”

The Hammer rolled her eyes. “Don’t worry,” she said. “I ordered knowing you’d want half.”

I tell you what. It’s nice to be known so well.

We continued on. Up the Goshen Canyon climb, and then across the rolling farmland. Making what felt like fantastic time to Nephi.

And we did, in fact, make fantastic time. In fact, we averaged 19.4mph for that 50+ mile segment.

We pulled up to the gas station / Wendy’s, knowing we had earned our first 10 minute break: a chance to use the bathroom, stretch our backs, and share some chicken nuggets and a frosty.

Then we got back on our road bikes, thinking we were ready for the next section of the race.

But there was no way we could have been ready for the disaster-after-disaster sequence of events that was about to begin.

And that’s where we’ll pick up on Monday.

Comments (42)

09.26.2013 | 7:46 am

A Note from Fatty About The Upcoming Spreecast: It’s canceled. So, um, never mind.

A Note from Fatty About Today’s Post: This is part 4 of my 2013 Salt to Saint race report. Here’s where you can find previous installments:

The Hammer and I started the descent down the south side of Suncrest together. We weren’t going aggressively; this wasn’t the ride for that. Still, I gapped her. Whether it’s the ENVE deep-rim wheels or just my very aero belly, If the two of us are going down the same hill and neither of us is braking or pedaling, I will leave The Hammer behind.

Once I got to the bottom of the steep part, I looked over my shoulder.

She wasn’t there.

I coasted another fifteen seconds or so and looked over my shoulder.

Still not there.

I got concerned. Ordinarily she would be visible by now. Was she on the side of the road with another flat? And if so, what would I do? I had already gone through both the tubes I had brought.

I looked over my shoulder and smiled. There she was.

I feathered the brakes ’til The Hammer had nearly caught me, then spun up to match her pace as she pulled alongside me.

As a good husband, I had no intention of asking what had happened. To do that is to imply that she had taken too long, had gone too slow. So my plan was to say nothing and just ride together. If there was something remarkable to say, she’d say it.

Seriously, folks, that right there is a hard-earned piece of wisdom you can use in riding with your friends and family. Feel free to thank me for it now.

“I got stung by a bee up there!” The Hammer yelled.

“Where?”

She pointed at one of her legs — I can’t remember which one, because I’m not that good of a husband — on the inside, just above the knee.

“I already got the stinger out,” she said.

“How’s it feel?”

“Like I just got stung by a bee.”

“Do we need to stop at the aid station or a grocery store (we’d be passing one in just a minute) and get anything?” I asked.

“No, let’s keep going.”

Yep, that’s right. The Hammer got stung by a bee…and let it cost her a grand total of twenty seconds of race time.

That’s The Hammer for you, ladies and gentlemen.

Jake and Jason, Part III

With me asking, “Does that sting hurt?” like, every twenty seconds, and The Hammer replying, “Yes, but I’m fine, let’s keep going” every time, we approached the second transition area, where we had originally planned to hop off our road bikes and on to our Specialized Shivs, for the mostly-flat ride around Utah Lake, up Goshen Canyon, and into Nephi, where we’d get back on to our road bikes for a while.

As we neared the transition, we started looking for anything we recognized. A big white truck, for example. Or an army-green Honda Ridgeline. Or Nigel. Or Jilene.

Or none of the above.

They hadn’t caught up with us. As far as we knew, they could still be stranded in a parking lot in Salt Lake City.

“They know where we’re headed,” The Hammer said. “They’ll catch us when they catch us. Do you need anything right now anyway?”

“Nope, my pockets are still full of whatever Jilene stuffed into them at the beginning of the race,” I said. Which, right there, was an admission that I was already sewing a tiny little seed of my own long-distance destruction: I had been out riding for about two hours and had not eaten a thing (nor had I had anything to drink).

“Well, let’s coast for a minute and eat something, then we’ll pick up the pace again.”

I pulled out something wrapped in foil, unwrapped it, and took a bite: a homemade pizza roll The Hammer had made from a recipe in Feed Zone Portables: A Cookbook of On-the-Go Food for Athletes.

That thing was delicious. So I pulled out another foil-wrapped package from my jersey pocket, unwrapped it, and ate that.

Blueberry turnover. Better than a Hostess (may it rest in peace) pie. Really.

“Baby, you have put a smorgasbord of awesome food in my jersey,” I said. “Eating during this race is going to be fantastic.”

About then, Jake and Jason — two of the guys who were also doing the Salt to Saint solo — rode up beside us.

“Why aren’t you about ten miles ahead of us?” asked The Hammer. It was not an unreasonable question, since when we had last seen them, they were riding away as we were stopping to change the first of two tubes.

“Oh, we just had a little lunch, got a little massage,” Jason (or Jake) replied.

And we fell into a paceline, going at the nice easy pace you’ll only find when four people know they will still be on their bikes the same time the next morning.

I would like to note that I picked out the primo spot for myself: right behind the 6′4″ Jake. Which reminds me: on behalf of all the short (5′7″) guys in the world, I’d like to thank all the big guys in the world who let us draft. You have no idea exactly how awesome that is, nor how little work we do when we are behind you. Seriously, I just stopped pedaling and coasted for a while.

“Hey, I’m happy to pull sometime,” I called out.

“Every little bit helps,” Jake replied.

Ha.

The Cavalry Rides Over The Hilltop

The four of us rode along, talking, enjoying what was turning out to be a really fantastic day for riding — a mild headwind, temperatures in the “just right” range.

And then we saw it.

Finally.

Our crew.

Coming toward us in my Ridgeline (Blake’s white truck was being towed to a mechanic) was Jilene, Nigel, Zac and Blake.

The Hammer and I cheered. Everyone in my truck cheered. Then they swung around, and told us they’d go forward a mile or so to get out our other bikes and stuff.

“I told you everything would work out all right,” I told The Hammer, though in reality I’m pretty sure she was the one who had told me that.

Support from a Unicorn

A mile or two later, we saw the Ridgeline, pulled over on the side of the road, with our Shivs ready to go.

But that’s not what caught our attention. This was:

This photo is a re-creation, since nobody thought to get a picture of it during the actual race.

Jilene had brought — among cowbells, hawaiian leis, and funny hats — a unicorn mask to wear as she was supporting us.

I was suddenly very bummed that we had missed most of what would have been hours of hilarious crewing antics. At the same time, though, I was glad that The Hammer and I have such great friends and family: people who are willing to support us as we do ridiculous races, and who we were able to confidently rely on to handle any problems that come their way.

All while being silly enough to wear a unicorn mask in broad daylight.

I pulled over, swapped onto my Shiv, asked Blake to please take care of getting new tubes and CO2 cans into the seat packs, and looked over at The Hammer. “You ready to go?”

“Yeah,” she said. “And I think it’s time for us to pick up the pace.”

Comments (43)

09.25.2013 | 6:45 am

A Note from Fatty: I’ll be doing a spreecast tomorrow. More details in tomorrow’s post, but allow me to recommend you clear your calendar tomorrow at 7pm ET / 4pm PT.

A Note from Fatty About Today’s Post: This is the third part in what promises to be a series with at least nine parts. But probably more like nineteen. Find Part I here, and Part II here.

Until last weekend, the greatest distance I had ever ridden my bike at a stretch was in the Seattle to Portland ride, which is right around 200 miles, is at sea level, and has virtually no climbing.

The Hammer’s previous longest ride was a popular regional race called “Logan to Jackson,” better known as “LoToJa.” It’s 206 miles.

Neither of us had ever ridden the Salt to Saint route, and neither of us had experience with the kind of distance we were trying out: 423 miles.

We didn’t know how we’d do with this kind of distance as far as food. Or hydration. Or exhaustion. Or clothing.

On top of this, I had had so little time to prepare for this race.

And so far, things were going so badly. We didn’t have a crew. We seemed to be prone to missing turns. We’d had one slight-yet-ominous mechanical.

So I thought I’d try using The Secret in conjunction with other superstitions to make things better.

“These kinds of things happen in threes,” I said. “And three bad things have happened. So now everything’s going to go smoothly.”

I did not, however, say this out loud, because it’s patently ridiculous.

Jake and Jason, Part II

As The Hammer and I reached the end of Wasatch Boulevard, we caught back up with Jake and Jason, two of the three solo racers who weren’t The Hammer and me (that was clear, right?). We struck up an easy conversation about how none of us had any idea of what we were in for, and that a nice easy pace was the order of the day. And hey, maybe we’d ride a bunch of it together, cuz here we were, riding at the same nice pace as each other, right?

Then we hit the end of Wasatch Boulevard. Which is worth mentioning for two reasons. First, the awesome thing about riding south on Wasatch Boulevard is how it ends: with a rocket-fast and arrow-straight descent. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if I got my highest speed of the day coming down it. But Jake — who looked like a very fit six-foot-and-a-lot-of-change — flew right by me. Then Jason did too.

We regrouped at the bottom of the hill and started riding together again.

Which is when The Hammer’s bike started ticking.

Pssssssst

“My bike just started making a ticking sound,” The Hammer said. I could hear it.

“Stop pedaling for a second,” I said, wanting to see if the rhythmic clicking came from the drivetrain or the wheels.

She stopped pedaling. The clicking continued.

“It’s a wheel,” I said. “Maybe it’s something in your spokes or….” I trailed off, not wanting to even mention the possibility of a broken spoke.

“No, I see it now,” The Hammer said. “There’s something stuck in my front tire.”

We slowed and stopped, waving Jake and Jason on. It seemed that there was some astral force that was absolutely positively against us riding with these really nice solo riders, and was going to do whatever it had to in order to keep us away from them.

I looked down and could immediately see what was sticking in the tire.

A goathead. Perfect.

“Maybe it didn’t go into the tube,” I said, hopefully, and pulled it out.

The rush of air out of the tire let me know that I was wrong.

The Hammer began apologizing. In a very formal voice, I accepted her apology (“I accept your apology; let us never again speak of this harm you did to me”), because I find that accepting peoples’ apologies when they don’t actually have anything to apologize for is strangely satisfying.

The nice thing about pulling out a goathead was, at least I knew exactly the cause of the flat, which meant I didn’t have to play detective, inspecting every square millimeter of the tire for the source of the flat.

I just took off the wheel, zipped the bead off the rim, pulled out the tube, put a new tube in — I was very glad I had taken the effort the night before to ensure that our saddle bags each had a tube and two CO2 cartridges — and inflate it.

But something went wrong with the first CO2 cartridge. The tire didn’t inflate. “Oh well, good thing I brought extras,” I said, then screwed in another cartridge and tried again.

This time I was watching more closely and saw: the CO2 cartridge worked fine. The new tube was at fault.

The tube was defective.

“This is not good, I said, because I had only one more tube with me: a road tube with an 80mm stem, for my deep-rimmed ENVE wheels. I wasn’t excited about using it on The Hammer’s wheel, cuz I didn’t have a huge number of these long-stemmed tubes.

I mean, I wouldn’t have many of them if our crewing vehicle were with us. As things stood, this was the only tube I had left to use.

So in it went. As I worked, I did the best I could to ignore the riders and crews zooming by as we dropped down to either last place, or something like it.

“You know,” I thought to myself as I finished up, “An 80mm stem poking out of a traditional box-type rim looks downright comical — as if a stem looked around and decided it wanted to grow up to be a spoke someday.”

The Crowd Goes Wild

Finally, we were at the base of Suncrest — the four-mile, 1300-foot climb that is, indisputably, the toughest pitch of the race.

Except the other side of it is about two miles from our house, so we’d been up this climb scores of times. In fact, since we went up it nice and gentle — honoring our promise to each other to never go into the red zone on this ride — this was the easiest climb up North Suncrest I’d ever had.

And so it felt very strange — although also really generous and nice — to have crews and family from other teams cheering for us and giving us encouragement.

“I don’t feel like I’m earning these cheers,” I told The Hammer. “Should I stand up and race hard up this hill?”

The Hammer just shook her head. That poor woman puts up with a lot.

The Person I Blame For This

As we rode up Suncrest, a guy pulled up alongside us on his motorcycle and matched speed with us. It took a moment for me to place him, because I’d only seen him on bicycles before.

Troy.

As in, “Troy, The Hammer’s friend who planted the idea of us doing this solo in The Hammer’s head.”

I knew that, twenty-four (or quite possibly fewer) hours from then, I’d resent Troy pretty strongly. But for now, it was great to see him and — since he had himself done the race solo in 2012 — pick his brain.

His strongest piece of advice: “Make sure you get plenty of warm clothes on for the big night descent.”

“I hope we have a crew by then,” I joked. At which point he volunteered his wife to be our temporary crew.

“Nah, our crew’s bound to catch up to us soon,” we said, hoping that our crew would catch up to us soon.

We reached the top of Suncrest. Now all we had to do was bomb down the 1200-foot, four-mile descent, ride a couple of easy miles to the aid station, and swap out to our Specialized Shivs, which we’d be riding for the next 70-ish flat miles, all the way into Nephi.

Except, of course, we had no idea whether our crew would be there.

And also, we had no idea that, three minutes into the descent, The Hammer would find out that her streak of bad luck was not over.

And this time, the bad luck was going to hurt.

Comments (37)

09.24.2013 | 6:19 am

A Note from Fatty: Part I of the report is here.

A Note from Fatty About the Salt to Saint Race Format: Quite a few people commented about the racer in the green shirt in the background of a couple of the photos yesterday. Sadly, I don’t know who that is. He does represent, however, one of the things I loved about this race, though: diversity of participants. The Salt to Saint allows soloists (like The Hammer and me and a few others), four-person, and eight-person teams. On an eight-person team, each racer does around 50 miles of racing, with plenty of time between turns.

Salt to Saint even has an open division, which allows you to propose your own number of racers on your team. For example, this year there was a nine-person team named “18-Wheeler,” which I thought was fantastic.

On another team, I saw a dad with a different one of his children on each of his legs of the race. This kind of team-size flexibility allows anyone to be a part of the race, instead of just people (like me) who have gone a little overboard with their biking (and racing) obsession. And with the reasonably short race segments (13-20 miles, if I remember correctly), most people don’t have to worry about whether they can complete their part of the race.

In other words, Salt to Saint is a total relay road race gateway drug.

Let’s Start Off By Going The Wrong Direction

So here’s what has happened so far, just to refresh your memory.

Our crew — and all our stuff — was stranded with a truck that had decided — for SECURITY’s sake — to not allow anyone to turn the key in the ignition. The race had started, and The Hammer and I had taken off after expressing our confidence to our crew that they would — somehow — either get the truck started or get someone else to the starting line, transfer all our gear over, and then find us on the course.

Well, at least that gave The Hammer and me something to talk about as we rode. Which was a good thing, because I have a problem when I race: restraint.

Or, more to the point, my problem is lack of restraint. Which is to say, I tend to take off as if the finish line is in sight, even — apparently — when the finish line is a ridiculous distance away.

Here, look:

Yep, that’s me on the left, standing up at the starting line, doing everything I can to not launch an attack.

Yeesh, what a dork.

[Side Note: You'll notice that neither The Hammer nor I have race numbers on these bikes. This is because our race numbers are on our Shivs, which we expected to spend most of the race on (but we wanted to use our road bikes for the first 50 miles or so, mostly because of the four-mile, 1300-feet Suncrest climb).]

But I did not launch an attack. No. We talked about the fact that we were in quite a predicament. And that it was incredibly weird for us because we are both planners and love to nail down every last detail of how we’re going to approach a race and now, here we were, at the beginning of the longest — by a factor of more than two — ride of our lives, and we couldn’t control anything. All we could do is ride, and trust that the people we had asked to take care of us…would actually find a way to take care of us.

And we were so absorbed in the discussion of what a strange start to the race this had been…that two blocks after the start of the race, we missed a turn.

We Meet Russell

In our defense, we were not the only people to miss that turn. We were, in fact, just being sheeple racers: following the line of the racers ahead of us. And about ten of us had just blown through a well-marked turn.

Who knows what would have happened if someone with keener eyesight and less of an inclination to just follow the wheels in front of them hadn’t yelled out? We’d still be out there, man. We’d. Still. Be. Out. There.

As is, we only went out of our way by fifty feet or so, and that would be the only wrong turn (OK, actually there would be one more, and it would be more extensive) of our entire trip; the Salt to Saint guys did a fantastic job of marking the course.

As we rode, we’d look at people’s race numbers. The Hammer told me we should be on the lookout for other racers with race plates from 52 to 54 (we were 50 and 51) — the other solo riders in the race.

A moment later, we caught up with Russell Mason, racer 54. We wished him luck as we went by, then I said to The Hammer, “Well, at least we’re no longer in last place.”

“Yeah,” she said, “But I wonder if he knows something we don’t. Maybe we’re going too fast and we’re going to blow up before we’re halfway done with the race.”

“I don’t feel like we’re going too hard. Do you?” I asked.

“No. And no matter how slow we go, we’re going to be sore and tired by the end of this race. So we may as well go at least at a medium effort. Let’s just try to never go into the red zone.”

We Meet Jacob and Jason

The Hammer and I kept on going at our nice medium pace, talking about how odd it was to be riding where we trained, but as a race. “We won’t really start counting it as a race ’til we get a hundred or so miles into it, OK?” The Hammer said.

We climbed up Wasatch Boulevard, a popular road for riding in our area, and that’s when we came across racers 52 and 53, Jason and Jake. “Hey, check us out. 80% of the solo riders are bunched up together!” I exclaimed.

“Are you riding together?” The Hammer asked.

“Sure, let’s work together, either Jake or Jason answered, misunderstanding her.

Still, it was a good idea, and we would have been happy to be part of a rotating paceline of four solo riders.

Except The Hammer’s chain chose that moment to fall off.

“Go on, we’ll catch you in a little while,” I said as they went by, although I had no expectation that we would actually catch them.

It took The Hammer only a few seconds to get her chain back on, although the fact that it had happened at all made me nervous. First the truck, then the wrong turn, then what could well be a problem with her front derailleur.

“This day isn’t starting out at all well,” I said. “A whole day’s worth of bad stuff has happened during the first hour of this race.”

And five minutes later, another whole day’s worth of trouble would begin.

Comments (37)

« Previous Entries Next Page »