06.13.2018 | 11:38 am

The Hammer was ahead of me, holding my phone and using it as a flashlight as we walked down the mountain. She was crying, with the only times she’d stop being when she’d gather air to yell her dad’s name again. Then I’d let five or ten seconds go and take a turn yelling his name, too.

I felt helpless, miserable. As useless and ineffectual as I’d been up on the mountain, I’d at least been somewhere near where we’d last seen Dee; I was looking for him.

Now I felt like we were abandoning him to the dark, to be alone on the mountain overnight, confused and lost at best, probably injured or incapacitated, and very likely dying or dead.

I didn’t tell Lisa where I thought her dad most likely was on that spectrum; she didn’t need to hear it and I didn’t want to say it.

The thought of going home, sitting there (certainly not sleeping) and not doing anything, made me feel ill.

Encounter

As we hiked down, we saw a man in a high-visibility shirt hiking toward us. Wearing a backpack. As he got closer, we could see he was with the search and rescue team.

Lisa and Kylie recounted what had happened that day and described Dee to the search and rescue man (I can’t remember his name). Kylie showed him a picture on her phone from earlier in the day, and the man took a picture of it with his phone (couldn’t send it; no service).

He assured us he and the rest of the search and rescue team would work through the night to find him, and a UHP helicopter with a heat-sensing scope would shortly be taking off. He assured us they’d actually have an easier time seeing him with that at night than a normal helicopter would during the day.

I was incredibly grateful for these people. For their positivity, for their competence, for their willingness to drop whatever they had been doing and do this instead, all through the night.

We all thanked him and he continued his march up the trail; we continued our trudge down it.

Encounter, Part 2

We hadn’t gone more than fifty feet before the man shouted at us, “Wait!”

We immediately turned around and ran toward him.

Even before we got to where he was standing, the man — now laughing — said, “Your dad just walked in his front door.”

What?

“Your brother called and said your dad just got home.”

And suddenly the whole world was better.

What Happened (We Think)

“I’m going to kill that old man,” was the first thing I said, but Lisa didn’t really think that was funny (although she’d say the same thing the next morning).

“I’m just so happy,” she sobbed, over and over. “I was sure he was dead, that I was never going to see him again, and he’s home instead!”

As you might expect, the remaining three miles down the trail in the dark went a lot more cheerfully than that first mile had.

At the trailhead parking lot, we took some time to thank everyone who had dropped everything to come help, then headed over to Lisa’s dad’s house, where first there were just hugs:

And then a little bit of throttling:

And of course Lisa asked, “All our lives, what did you tell us to do if we got lost or separated while hiking?”

“To stay put,” her dad replied, knowing what was coming next.

“AND WHAT DID YOU DO?”

“I just kept going,” her dad replied. Chagrined.

And that’s really what happened.

With his poor eyesight, Dee had mistakenly walked off the trail onto an old deer trail. Then, when it petered out about twenty feet later…he had just kept going, walking down the face of the mountain in deep scrub oak.

Eventually — and I’m sorry I don’t have a lot of detail to give you here, because Dee hasn’t been able to give us much detail — he wound up close to the bottom of the mountain and near a neighborhood, but trapped in a ravine.

Which is when a couple of hiking teenagers came across him.

“Are you OK?” they asked.

“No, I’m stuck and I’m lost!” Dee told them.

The kids helped him out and then walked him down to their car, then gave him a ride home.

One of Lisa’s relatives snapped this photo of them together:

We don’t know their names, we don’t have contact info, we aren’t even really sure where he was when they found him.

But we sure are glad they were there and took care of him.

So many heroes that day. And I’m incredibly grateful for all of them. And that this worst of all possible Thursdays turned out, in the end, to be a great story worth telling over and over.

Comments (16)

06.12.2018 | 9:03 am

Let’s conduct a little thought experiment: suppose 25 years ago you picked up the Leadville 100 race course, and set it down in California. Would it have become the iconic endurance race it is today?

I suggest it wouldn’t have.

The altitude is what makes this race special. It turns what would otherwise be a hard race and turns it into a mystical, confounding, and — for some people — darn near impossible race.

So a couple weeks ago, I met with and interviewed Dr. Colin Grissom. Dr. Grissom is the co-medical director of the Shock/Trauma ICU at the Intermountain Medical Center in Salt Lake City, but he’s also a well-known pulmonologist, mountain biker and high altitude climber, including mountain climbing in the Himalayas, and has done altitude research on Mt McKinley.

I was SO EXCITED after talking with him that I couldn’t wait — I made a rough audio mix (i.e., I just merged the two audio channels from our mics, didn’t worry about levels or anything else) for The Hammer (who had helped me find and arrange a meeting with Dr Grissom) to listen to that evening.

She listened, and then looked at me and said, “That is the single most valuable interview anyone who is ever going to race Leadville could ever listen to.”

We’ve each listened to it a couple more times, taking notes.

So. While I truly believe all my Leadville podcasts are must-hear, let me say this: if you think you might ever race Leadville, or crew for someone at Leadville, or may just go vacationing at altitude, you don’t want to miss this episode. You just don’t.

But that’s not all there is in this episode. In Our Questions for the Queen segment, Rebecca Rusch gets gross, talking about how to keep going when you have GI issues.

In our segment on The Course, we talk about road tactics on Hagerman, as what is often acknowledged as the best part of the race: Sugarloaf.

And finally, Jonathan Lee’s training advice will — finally — cut you a little slack.

Thanks to Our Sponsors

We went out of our way, for this podcast, to reach out exclusively to companies we actually love and buy stuff from ourselves. Which is to say, you won’t find ads here for life insurance companies or mattresses or cooking kits that come to you in a box. These are all companies I buy stuff from and use pretty much every damn ride.

Please support them or I will cry.

Shimano

Shimano

The Hammer and I are both terrible mechanics. I mean, truly awful. So we’re hedging our gear bets for when we race seven days straight (Breck Epic and Leadville) this year.

First, we’re each bringing three bikes: our Specialized Epic full suspension bikes, which we have at this point planned to race all 7 days on if at all possible. As backup, we each have geared hardtails. And as final secret bonus backup we each have our trusty singlespeeds. (If you see either of us on a singlespeed any of the seven days, you know things have gone seriously wrong.)

But I’m thinking / hoping that our Epics are going to be fine for the whole seven days, and a lot of that has to do with my experience so far. Specifically, Specialized Di2 just feels bombproof. Neither of us have needed any service to our drivetrains since we got these bikes back in April. Same thing goes for our XT cranks, brakes, and pedals.

Now, both the Hammer and I are kind of cautious and are easier on our gear than some, but I’ve been riding with other companies’ MTB drivetrains for a couple years leading up to this last Spring, and I never had as reliable of an experience as we’ve had this year. I’m super glad we’re riding and racing Shimano this year.

The Feed:

The Feed:

Last weekend, Hottie and I each used a variation of Maurtens drink mix on our big rides. And both of us are totally sold on it. No stomach issues, goes down easy, super easy to mix. Hottie’s super anal about stuff like this, so he loved the package precision; they tell you exactly how much water to use, no guessing with scoops and different sized bottles.

My overarching impression is that it’s a ridiculously non-intrusive way to get down a lot of calories. One bottle, 320 calories — it’s a little sweet, it’s a little thick, but there’s no aftertaste and I felt great — my stomach was fine, I didn’t feel that weird energy spike you get with some energy drinks. It tastes smooth, and it burns smooth. I am a fan.

And our podcast listeners can get a great price on a training and racing packs custom curated for Leadville racers. Go to TheFeed.com/leadville for the race pack, and there’s a link on that page to go to the training pack. And be sure to use the code LEADVILLE15 for a 15% discount on either of those boxes.

Banjo Brothers

Banjo Brothers

At Leadville, and at any race, you will see riders with all sorts of crazy ways to carry their bike repair essentials. People tape or velcro stuff to top tubes, stems, seatposts and seat tubes. We say do yourself a favor, use our sponsor, Banjo Brothers, to get your flat fixing goodies strapped properly to your bike.

And not just your race bike, but your commuting bike and your bikepacking bike…and they’ve even got great backpacks and messenger bags for when you’ve got to carry bigger stuff.

I’ve got a Banjo Brothers Bag on every bike I have, and have been for a dozen years. They’re simple and they’re bombproof. They just work.

To get 15% off your order, go to Banjobrothers.com/fatty-favorites.

ENVE

ENVE

I know we’re not talking about the Powerline descent ‘til next episode, but I want to preview an interesting fact about this descent. In my twenty finishes of this race, I bet I’ve passed more than 200 people on this section of the race, all of whom are faster than I am. Because they’re all stopped on the side of the road, coping with pinch flats.

But neither The Hammer nor I have pinch flatted even once since we’ve been riding with ENVE M525 wheels. It’s the wide hookless bead that really does the trick here. ENVE has a really wide leading edge for the hookless bead, and this broad surface creates a more forgiving platform on which the tire can bottom out, and proves extremely effective in reducing the likelihood of “pinch” flats. And with a lower risk , you can ride with lower pressures, which gives you better traction and rolling resistance.

For example, I’m currently 167 pounds and running 19lbs in front and 20 in the back. The Hammer is running 18 in front, 19 in back.

I mean, wow.

Comments (4)

06.11.2018 | 9:12 am

A Note from Fatty: If you haven’t already, you should read Part 1 and Part 2 before reading this part.

We were all gathered now — Lisa, Blake, Kylie, me, and Austin (the cop), at the last place Lisa had seen her dad. But two hours had gone by since he had been here, and — obviously — Dee was somewhere other than where we all were.

Lisa’s brother Scott joined us, having hiked over from Squaw Peak — since it was a mountain Dee knew well, it seemed possible he would have headed in that direction. A good idea, but no luck.

Blake and Scott trudged off in one direction together. Lisa and Kylie stayed close to where they had seen their dad most recently. I stood near Austin, looking down the face of the mountain into Utah Valley. Austin he talked on the radio, asking for the Life Flight helicopter to come over and to get search and rescue in motion. I was just hoping I’d hear anything useful that came over his radio.

The helicopter appeared and landed in a field in the valley. It couldn’t fly until a couple of paragliders got out of the area. Once they landed, the helicopter took off and started flying back and forth, scanning the mountain.

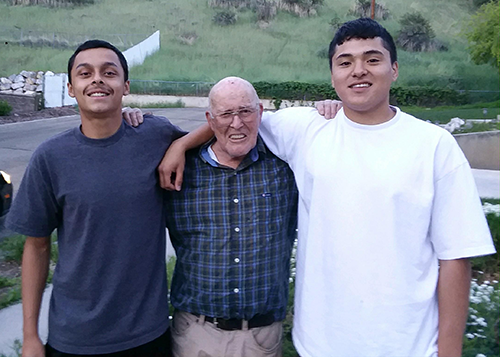

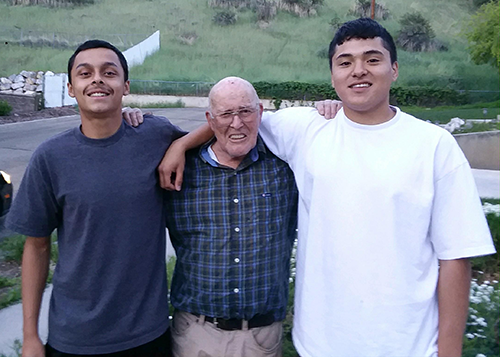

“You’d be amazed at how much they can see,” Austin said, somehow anticipating my question: “Is there any way they’ll be able to see a man wearing a neutral-colored hat and muted colors for both his shirt and pants?” (In case you’ve forgotten, Dee’s the one on the right in this photo — not exactly day-glo clothing.)

“You’d be amazed at how much they can see,” Austin said, somehow anticipating my question: “Is there any way they’ll be able to see a man wearing a neutral-colored hat and muted colors for both his shirt and pants?” (In case you’ve forgotten, Dee’s the one on the right in this photo — not exactly day-glo clothing.)

None of us knew what to do, and none of us wanted to acknowledge that it was getting dark, nor what that implied.

But the truth was: we weren’t dressed for how cold it was getting. I wasn’t dressed for being outside at all.

Finally, it was Austin who told us: “You’d better head down, guys. We have a team up here and we’ll find him.”

So we started heading down the trail, yelling Lisa’s dad’s name, knowing that he almost certainly wouldn’t hear us; his cochlear implant hadn’t really done much to improve his hearing even before his stroke. Now he hears — or understands — even less.

It got to be fully dark. I got out my phone, which fortunately still had close to a full charge. It makes a not-half-bad flashlight, at least for a while.

We came across the first search and rescue person before we were a mile down. “We are going to search through the night. We’ll find him,” the man assured us. I’ve never been so grateful for positive confident words like that, and I was glad Lisa heard them.

We continued down, Lisa crying most of the time. I was keeping a tight filter on my words, because I didn’t want people to hear what I was thinking: “It’s cold and dark and he has no light or water or a jacket or anything. I worry he won’t survive the night.”

I knew we were going home to the likelihood of just sitting and worrying through the night. Sleep wasn’t a remote possibility. We’d drive back here before it got light to start searching.

But I was terrified of what kind of condition he’d be in when we found him.

And we’ll pick up there in the next (and final, I think?) installment of this story.

Comments (6)

06.8.2018 | 11:01 am

A Note from Fatty: For those of you who expected the next installment of my “Worst Thursday” series, that will come out Monday. Meantime, why don’t you enjoy this podcast instead? It’s a story-based episode, and definitely a story anyone can enjoy. – FC

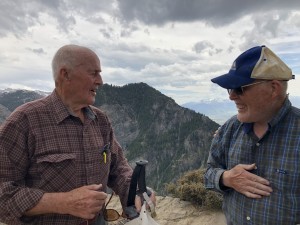

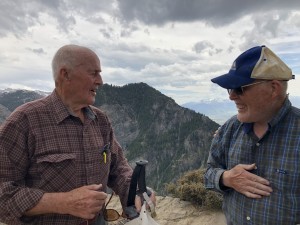

In August 2015, I had the best day of my life, race-wise. That’s the year I finished the Leadville 100 in 8:12 minutes. I of course wrote a lengthy race report, including — in part 7 — a little digression about Dave Edwards, one of the really cool people who played an important part in my once-in-a-lifetime day. Here’s Dave and me — at this point basically complete strangers — a couple days before the race:

Dave had grown his hair, a la Sampson, as part of a complex set of negotiations with his wife. The end result was that he wouldn’t cut his hair until he crossed the finish line.

But things didn’t go as planned for him. In spite of all his training and planning, he missed the 40-mile cutoff and his race day ended before he was ready for it to end.

Which of course is sad, but which, in my opinion, also makes his story more relatable and compelling.

You hear from me about this race all the time, and with 20 of them completed, I can no longer really speak with conviction about the anxiety most racers have about this race: whether they’ll cross the finish line. I don’t remember how utterly crushing the altitude can be the first time you arrive in Leadville.

But Dave remembers, and I’m incredibly pleased to have finally heard and recorded his story as the first Friday Bonus Episode of the Leadville Podcast.

If you’ve thought about doing this race but haven’t yet, or if you’ve never considered (and will never consider) it but are curious what it might be like, Dave’s story is a great one to hear.

Please listen, subscribe, and let me know what you think!

Comments Off

06.7.2018 | 9:16 am

A note from Fatty: Part 1 is here. If you haven’t read it yet, read it before reading today’s post.

Lisa’s dad, Dee, was gone. And now, by running around off-trail in the thick mountain scrub oak, Lisa was lost, too.

Lisa didn’t have her phone with her, either. She had left that, along with everything else, with Kylie when she took off running, looking for her father.

And it was starting to rain.

Lisa was now truly terrified. Cold, lost, and no closer to understanding where her father could be. And no way to call Kylie to tell her to call 911. To tell Kylie that she wasn’t sure where she was.

One Good Thing

And then Lisa’s watch rang. Because her watch is also a phone. Which, in her panic, she had forgotten.

It was Kylie. She had called 911. The police were on their way.

So now Lisa just needed to find the trail, stay warm, and hopefully find her dad.

And then Lisa’s watch died. Strava, it turns out, is not kind to the Apple Watch’s battery.

Going Up

Blake (Lisa’s son), Scott (Lisa’s brother), and I got to the trailhead at the same time, maybe 4:30pm or so, by which time Dee had been missing for an hour (or more? My memory of the timeline is fuzzy and for sure inaccurate). By now, though, nobody thought this was a wacky misunderstanding and that he’d turn up any minute.

Kerry (Lisa’s other brother) was already there. Scott and Blake had thought to pick up several coats at someone’s house (Dee’s, I think?), along the way. I was glad to take one; Lisa had told me it was cold and raining up on the mountain.

Kerry stayed at the trailhead parking lot handling logistics — police and concerned family communications — while Scott, Blake and I headed up the trail.

Before too long, a policeman on a police dirt bike came down the trail toward us, lights on. We stopped him, explained who we were, and Austin — the cop’s name is Austin — told us he’d been to the end of the trail but hadn’t found anyone.

We called Lisa — who had found her way back to the trail and was now reunited with Kylie, and she explained to him he needed to take a left at a fork early in the trail and then continue up the trail “that has a lot of bridges.”

Austin’s eyes widened. “You have an 86-year-old and 89-year-0ld at the top of that trail?” he said.

“These aren’t ordinary old men,” I said. “They’re more physically fit than most men half their age.”

And then I told him why I stressed the “physically” in “physically fit.”

Last October

Until last October, Dee had lived on his own. He had lost his wife during the summer, but he had his family close by and was still perfectly capable of taking care of himself.

Then one morning his sons came by to find Dee’s house trashed and Dee about to leave the house in his socks, making no sense at all. They called Lisa, who told them to call an ambulance immediately; Dee had almost certainly had a stroke.

Which was correct.

Dee recovered well in many ways. His mobility is unaffected and his personality is intact. But he’s more easily confused, he doesn’t reason as well, and his vision is severely affected.

And that, more than anything else, was why Lisa was panicked. It was so easy to picture him as having had another stroke. Or having fallen. Or just not being able to see what was in front of him and wandered off.

And since he has never been able to make heads or tails of the smart phone Kerry gave him for his birthday last year, and the cochlear implant has never really worked great, yelling and calling for him weren’t going to do much good either.

Austin went up on his motorcycle. Blake and I followed, hiking. Scott turned around and went back down; he was going to drive around and approach the mountain from Squaw Peak, looking for his father from a different direction.

Hope, Briefly

Blake and I and hiked up the increasingly steep singletrack, which I had never been up before. “Those old men really hiked this?” I asked Blake. “That’s insane.”

“Now you know where my mom gets it,” Blake said, although he knew I already knew.

We trudged up, my feet already hurting — having come directly from the office, I was not wearing shoes (or any other clothes) made for this kind of hike.

And then we saw a young woman, hiking down toward us with an old man. An old man who looked a lot like…Dee.

But it was Dee’s brother, Keith. Walking down the mountain in the company of a nice hiker who had volunteered to get him down off the mountain and out of the rain.

“I hope you find him safe and sound,” Keith told us. “But I suspect foul play.”

Up the Trail

Blake and I marched up the four miles of the trail, mostly keeping conversation light. I don’t know what was in Blake’s head, but I was trying to avoid thinking about the central thought: If Dee wasn’t on the one and only trail going up and down this mountain, he was off that trail, and there was no way that was going to end well.

I kept thinking about how I’d told Lisa, more than once, “Your dad is going to die while hiking.” Any time I had said it, I had meant it in a positive way. That he was such a strong old guy that he was going to be one of the lucky few people who died doing what he loved best. I’d go on to say I’ve always looked up to how tough he is, and have hoped that I’ll be able to keep that kind of fitness, so I can maybe die doing what I like doing.

I had a feeling that Lisa was revisiting my words and not finding any comfort in them at all. (Later, once this was over, Lisa told me I was right.)

We got to a steep, rocky section and. found Austin’s parked motorcycle — he wouldn’t be able to take it any further. Half a mile later, we found his bulletproof vest. didn’t need that, either.

Eventually, we got to a meadow and caught up with Austin, and called Lisa to find out how close we were. “I can hear you in real life, not just on the phone,” she answered, so we were close.

A moment later we were together: Kylie, Blake, Austin, Lisa, and me. Lisa hardly noticed Blake or me. I’ve never seen her so distressed, and hope to never see her that way again.

It was about 6pm. Maybe two hours of daylight left.

“I’m going to get the Life Flight helicopter out here to look for him and activate Search and Rescue,” Austin said.

And that’s where we’ll pick up next time.

Comments (5)

« Previous Page — « Previous Entries Next Entries » — Next Page »