08.5.2010 | 10:30 am

Susan died a year ago today. I’ve been grappling with a few thoughts. None of them especially deep, but here’s what’s on my mind.

- I think Susan would be happy with where I am. Susan and I had some very frank — but private — conversations during the times she was lucid. I think about these often, and am pretty frankly amazed at how some of the things she said she wanted have happened. My life is good now, the kids are doing well. Susan would be happy about that.

- I’ve avoided letting Susan’s biggest worry happen. Several times, Susan told me that she was worried that I would let her death change me, turning me into an angry and bitter person. That’s the opposite of who I’ve always been, and she didn’t want me to, in effect, become someone else. She wanted me to stay who I am, and I have. I’m proud of that.

- I don’t want this day to be a big day. It’s school break right now, and so the kids don’t even look at calendars (in fact, I’m pretty sure they studiously avoid looking at the calendar, so as not to have to think about the fact that later this month they’ll be back in school). The important thing about Susan wasn’t her death, it was the way she lived. So while I will talk with the kids today, I don’t think I’ll make it a big day. I think maybe Susan’s birthday is a better, more appropriate day to celebrate her life.

Comments (147)

08.3.2010 | 8:23 am

A Kidney Transplant-Related Note from Fatty: Many of you helped me raise money to help out my sister and her son as they went through an incredibly difficult kidney failure. I think you’ll all be excited to know, then, that last Thursday, my sister Kellene successfully donated a kidney to her son, Dallas. Since then, Dallas has been recovering at a remarkable rate, with signs that he and his new kidney are going to be get along just fine. Kellene’s out of the hospital now and in a lot of pain, but she’s tough. She’ll be home and riding again soon.

Once again, thanks to everyone who helped!

On August 14 — just eleven days from now — I’ll start the Leadville 100 for the fourteenth time. And, provided I have a good day, I’ll finish — for the thirteenth time (remember, I didn’t finish last year) — a while after that.

This is my plan for what happens between when I start, and when I finish.

My Overarching Race Day Philosophy

Every year, I seem to have a certain goal for the Leadville 100: Sometimes it’s been to finish it in under ten hours. A few times it’s been to finish it in under eleven. When I’m really fit, it’s to finish it in under nine hours.

Of course, that’s never happened.

This year, however, I’m not bringing a time objective to the race. I think that’s because something’s changed. Maybe it’s because I’m mellowing with age. Maybe it’s because for the first time in a long time I’m riding for fun instead of to vent pent-up anger and frustration. Maybe it’s just because I’m looking at the data and facing the facts.

Or maybe it’s just that I’m getting a weird thing called “perspective.”

At the beginning of spring and throughout summer, I asked myself a question: what kind of memories do I want to have when the snow starts falling (hard to even consider when it’s 100 degrees outside, but it’s never more than a few months away)?

Memories of training hard? Or memories of having fun on my bike?

Some years, those would have been the exact same thing — there have been years when pushing myself to the absolute limit gave me intense joy and pride.

But not this year.

This year, how I’ve defined “fun” on my bike has been to go out riding with my wife. We’ve ridden a ton together, and I’ve had a blast. I haven’t done a single interval, and I don’t care. It’s been my favorite riding season ever.

As a result, I’m in good riding shape, but don’t have the eye of the tiger (nor the thrill of the fight). I’ll finish the Leadville 100, probably in about ten hours (though to be honest with myself, I’d like to keep it under ten hours). I’m going to race it hard, but if I find myself riding alongside someone who doesn’t mind talking for a few minutes, that will be just fine.

And I will do my best to have fun.

What I Will Ride

I briefly considered riding a geared bike at Leadville this year, but once my FattyFly frame arrived, that pretty much ended the debate.

And now that I’ve got it all tricked out with Shimano and PRO components, the debate is really ended. Check it out, all nice and dirty from yesterday’s ride (click image for a larger version):

PRO XCR stem and PRO XCR seatpost, along with XTR cranks and brakes make this about as nice a bike as can be imagined. Factor in the Bontrager XXX Carbon wheels, the Niner carbon fork, and the Salsa Pro Moto bar, and I’ve got a bike that weighs well under eighteen pounds.

Sure, I’ll get beat to death on the downhills, but the climbs should be nice.

Oh, and for those of you who were going to ask: 34 x 20.

What I Will Eat and Drink

I usually obsess over what I will eat at Leadville. This year, for some reason, I’m not obsessing over it at all. Maybe that’s because I have stopped looking for a magic bullet. Here’s what I’ve been carrying with me on long rides lately, which will be the same thing I have at the aid stations in Leadville:

- CarboRocket

- PRO BARs: I’m a huge fan of Art’s Original Blend. A bar that doesn’t look and taste like it was extruded from a gross vat of goo, then left to harden for ten years before packaging it? Genius!

- Clif Shot Bloks: Tropical Punch and Mountain Berry are the best.

- Campbell’s Chicken and Stars soup: Sodium-tastic.

- Water: Sometimes, nothing tastes better.

- Several mayo packets. Just in case.

Pretty easy, and I haven’t had an upset stomach with this mix of food the whole year.

How I Will Ride

Up at 10K+ feet, it’s not easy to remember stuff. Hence, I have condensed my riding strategy into easy-to-recollect bullet points, as follows:

- I will fight the urge to pass a bunch of people during the St. Kevins climb. Every pass on that climb costs three times as much energy as a similar pass anywhere else on the course.

- I will not look at my bike computer more than once every fifteen minutes. At least during the first half of the race. During the final ten miles of the race, I reserve the right to look at it every five seconds.

- I will be friendly and yell encouragement. But I will try to keep that urge under control, so as not to frighten other racers. And bystanders, for that matter.

- I will not mention that I am riding a singlespeed to anyone who does not mention it first. However, I reserve the right to grimace and strain as I pedal, in the hopes that people will take notice and look at my drivetrain.

As always, I appreciate any guidance you would care to lend me. After all, I’ve only done this race thirteen times; I’m still kind of new at it.

Comments (63)

08.2.2010 | 12:12 pm

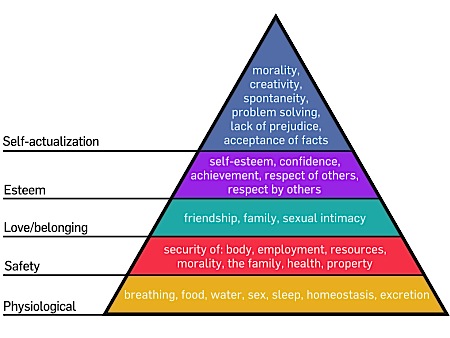

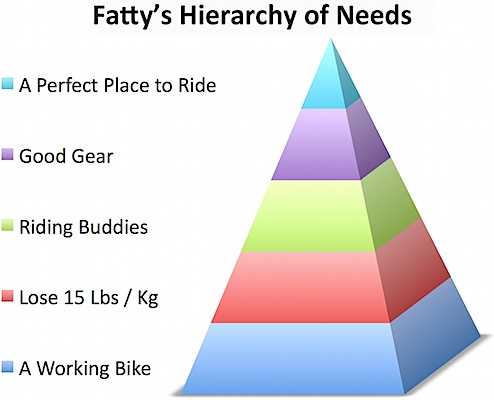

Abraham Maslow is famous for creating the “Hierarchy of Needs” — a graduating set of general requirements for human motivation. Like this:

The idea behind this pyramid is that you need to fulfill the needs in the lowest (Physiological) level of the pyramid before you start thinking about the needs in the second-lowest (Safety) level. Then you can move on to the Love / belonging needs, and so forth.

Then, hopefully, once you have satisfied the needs in the first four levels, you can start working on self-actualization, at which point you are a fully-realized human. Which would be, I assume, awesome.

Sadly, however, this hierarchy is woefully out of date.

Updating the Hierarchy

Now, I’m not slamming on Abe (Maslow’s friends called him “Abe”); back in the 40’s, this was a pretty good scale.

Since then, however, things have changes. Specifically, mountain bikes have been invented (thanks, Gary!), and road bikes have gotten much, much better.

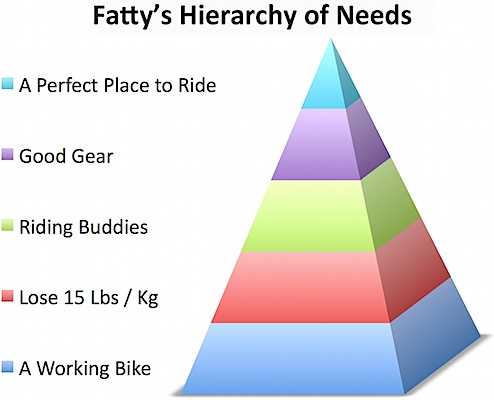

And hence, our needs — and the order of precedence and priority for these needs — have changed. Which is why I am happy to present:

You can tell that my hierarchy is superior to Maslow’s, just from a quick glance. For example, where Maslow’s pyramid is only two-dimensional, mine is three-dimensional. Where his uses stodgy, overly-saturated colors, mine uses eye-pleasing gradients. And my pyramid has an attractive shadow.

There’s more, of course. Mainly, my hierarchy is much more relevant and meaningful to today’s cyclist.

Fatty’s Hierarchy, Explained

I shall explain the needs of the cyclist, beginning with the lowest level.

- A Working Bike: Before all else, the cyclist must have a bike that can be ridden. The tires must be able to hold air. The brakes must stop the bike. The crank cannot creak so loudly that the cyclist loses his or her mind when riding. The bike must fit, at least sorta. In the absence of a working, rideable bike, the cyclist simply ceases to exist and becomes a much lower form of life (i.e., a non-cyclist). In short, having a rideable bike is the most important thing in the world, which is why many cyclists amass a sizeable collection of both bikes and bike parts — if one has enough bikes and components, one need never step outside to begin ride only to find an unexpected and catastrophic mechanical problem, thus causing one to — for all intents and purposes — cease to exist.

- Lose 15 Lbs / Kg: Any cyclist that says she or he rides strictly for pleasure is a liar. The truth is, all cyclists have an event or race in the back of their minds, and they have a goal for that event or race. And to achieve that objective, the cyclist must lose either 15 pounds or kilograms. Also, cyclists know that their clothing — specially designed to be embarrassingly revealing — is going to look a lot nicer if they lose that fifteen pounds (or much, much nicer if they lose 15 kilograms). And they’ll be able to beat people to the tops of climbs. And they’ll be able to get into their drops without their knees pushing all the air out of their lungs.

- Riding Buddies: Once you’ve got a bike in working order and have lost (or at least frequently talk about losing) that fifteen pounds / kilograms, you will naturally try to find a group of like-minded individuals. Individuals who will not condemn you for the way you spend all your time, money, and mental cycles on doing something you learned to do when you were five. Individuals who agree it is not even remotely pointless to expend a huge amount of energy and time to go in what is, invariably, either a loop or out-and-back, arriving exactly where you left, except much more tired. Individuals who are enough like you that when you’re around them, you can convince yourself that you’re normal.

- Good Gear: Once you have the basics of cycling down — a working bike, good fitness, people who share in your warped perception of priorities and fun — you will no doubt want to recapture the extraordinary feeling you had the first time you rode a decent — i.e., a non-big-box-obtained — bike. You will need a lighter bike, nicer components, an expensive pair of shorts with an anatomic wicking antibacterial chamois, and handmade Italian shoes. The more you spend, the easier it is for you to convincingly imagine that you notice a difference.

- A Perfect Place to Ride: The ultimate expression of a cyclist’s needs is the perfect route. What that perfect route is depends on the rider (although it has been widely rumored to be Tibble Fork in American Fork Canyon, Utah). Paradoxically, you may have — in fact, almost certainly will have — ridden the perfect route many times before you discover that it is, in fact, perfect.

I am looking forward to your reactions supporting this hierarchy. (I would also look forward to your reactions rebutting this hierarchy, but since is perfect, there can of course be no convincing counterargument.)

Comments (49)

07.30.2010 | 8:18 am

A few weeks ago, Chuck Ibis was in town as part of the Ibis Demo World Tour. It seemed like a good time for us to finally get together and do something we had talked about for — literally — years: go on a mountain bike ride together.

Yeah, considering that I’ve been friends with Chuck for years and years (Ibis has been a huge supporter of Team Fatty’s fight against cancer) and have been an Ibis junkie pretty much since I’ve started riding (I’ve owned a Steel Mojo, a Bow-Ti, a Ti Mojo, a Silk Ti, and a Silk Carbon), it’s strange that we’ve never gotten together for a ride ’til now.

OK, maybe it’s not all that strange, but that’s the conceit I’m kicking off with, so let me have it, OK? Sheesh.

And when people visit here, looking to see what my backyard riding is like, I always — whether they want to go road or mountain — take them up American Fork Canyon. For one thing, it’s genuinely one of my backyard mountain bike rides.

For the other thing, it generally makes people incredibly jealous of where I live.

And Now for Something Completely Different

Ricky M and I met the Ibis guys up at the Timpooneke trailhead, the Ibis guys driving a van that looked just as suited for covert surveillance as for holding a whole buncha high-end bikes:

(Kirk Telaneus on the left, Chuck on the right)

Both Ricky and I have been riding hardtails — usually rigid SS — lately, so Chuck and Kirk said we needed to switch things up: Mojo SLs for both of us — plush full suspension and gears galore.

Here’s Ricky supervising as Chuck sets up Ricky’s bike.

Hey, it’s not every day you get a Mountain Bike Hall of Famer to be your own personal mechanic.

I should note at this point that if you ever consider converting your Fat Cyclist jersey into a sleeveless, you may want to consult Ricky on how to do it so that it looks like your bibshorts look like a bra strap. Nice look, Ricky.

Oh, and here’s Chuck, setting his shock pressure to 10,000psi.

The Hills are Alive

There’s nothing quite as lovely as being acclimated to riding at 7000 – 8000 feet and then taking a Californian out for a ride. It does wonders for your ego. Kirk and Chuck didn’t have any difficulty hanging with Ricky and me, but they did call attention to the fact that they were feeling it a lot more than when they rode at home.

And also, they expressed appreciation for the fact that AF Canyon is just an incredible place to go riding:

(Chuck, wondering how in the world the Matterhorn got relocated to Utah)

(Kirk and Chuck, doing synchronized posing. Look for it in the 2012 games in London.)

(Chuck and me, showing off the Mojo SL and some beautiful scenery. Yes, he’s really that much taller than me.)

Different is Good

I’m convinced that the best way to appreciate the capability of a full suspension bike is to ride a fully rigid bike for a couple years, then hop onto aforementioned full suspension bike.

Because Ricky and I were just grinning and laughing as we bombed the downhill portions of the ride. Just letting the bike go, hitting stuff you’d normally avoid. Letting the suspension do the work.

After flying down Joy in what felt like record time, I turned to Ricky and said, “You know, I am not having any trouble at all picturing a Mojo in my stable.”

“I was just thinking the same thing,” Ricky replied.

Which is undeniable proof of two things:

- The Ibis Mojo is a terrific mountain bike, and riding one makes you want one.

- I will never ever be satisfied with the number of bikes I own.

Ow

As the ride went on, Ricky and I were more and more confident on our Mojos, taking more aggressive lines and letting the suspension do its job.

We were, perhaps, getting a little reckless. But we didn’t crash. Not even once.

And then, finally, we got to the final downhill. For this one, I knew I should take it more cautiously, because the trail is full of loose rocks, mixed in with plenty of embedded ones. And you never know which rocks are going to slide out of your way, and which are going to stay put.

I picked my way carefully and cautiously. Not exactly mincing, but not aggressive.

So of course I crashed. Good and hard. Taking most of it on my right knee. Here’s my bloodied up knee, artfully framed by the Mojo…erm…frame:

Not Ironic

As I rode — all the wind out of my sails now — back toward the trailhead, I thought about it: how ironic that I’d be just fine when riding aggressively, but crash once I got cautious.

And then I reconsidered. Maybe — probably — it wasn’t ironic at all. In fact, it was probably downright causal. Sure, I’ve had crashes when riding hard, but I have a suspicion that I’ve had just as many — maybe more — when riding overcautiously.

And I can’t even count how many times I’ve had a second crash during a ride because I’d become hypertentative following my first crash.

The problem, for me, is that this lesson is only easy for me to learn — and I’ve learned it several times — in my head. I know that riding tentatively just makes you more likely to crash, but when I’m nervous of a trail, I just can’t seem to convince my body to stay loose. Nor can I seem to convince my hands to stay off the brakes.

Which explains why I have scars on top of scars on top of scars on my knees, I guess.

PS: I still want a Mojo.

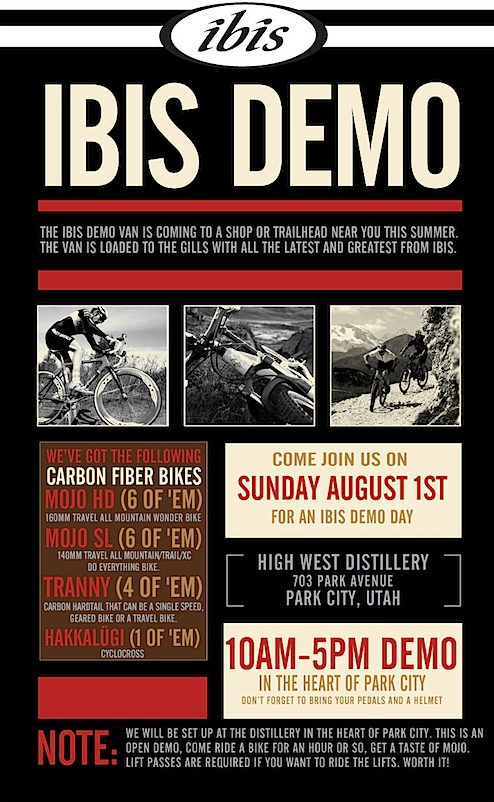

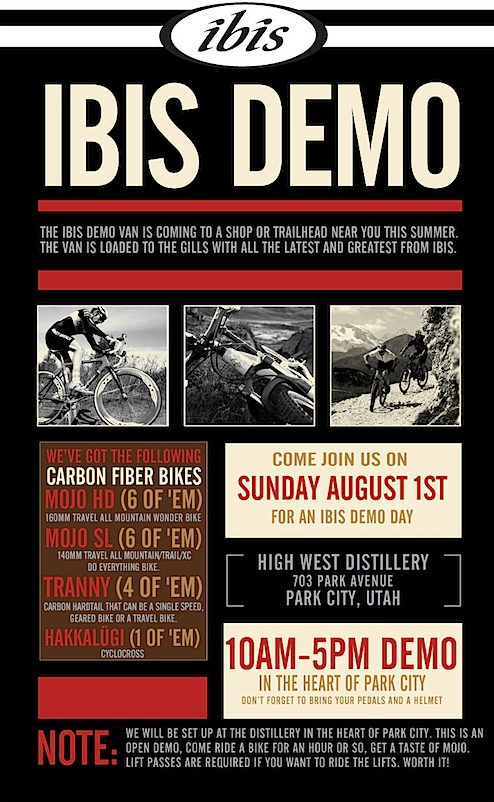

PPS: If you’re a Utah local and you’d like to try a Mojo SL, Mojo HD, Tranny or a Hakkalügi out, Chuck and Kirk are going to be in Park City this Sunday, with a whole buncha bikes for your demo-ing pleasure. See below (click the image for larger version) for details of where and when.

Comments (33)

07.28.2010 | 6:32 am

A Note from Fatty: I’m pleased to announce a new series, wherein I explain difficult cycling techniques and technologies in clear, simple English. Except for when it makes better sense for me to explain in French, in which case I will of course explain in English anyways, because I don’t know French.

If you have a cycling-related question you would like explained, simply email me. Due to the volume of email I receive, however, I cannot respond to all questions individually. In fact, I to hardly any of it.

OK, the truth is I haven’t checked that email address in months. But I will soon. I promise.

And now, on with the explainification!

What is Carbon Fiber and How Does It Work?

I recently received an email which I had slightly less-recently sent to myself. This email went as follows:

Hi Fatty,

First, let me begin by saying that I’m a big fan of your blog. I don’t know how you come up with your insightful, witty, and down-to-earth cycling commentary on a near-daily basis. The only person I’m aware of who writes more about cycling than you is Lennard Zinn. Oh, and Bike Snob NYC writes more than you, too. So that’s two people who write more cycling-related stuff than you. And they’re both better than you, too. No offense.

Anyway, the reason I thought I’d email you is to ask a question that’s been bugging me lately. It seems that more and more biking stuff is made from carbon fiber. Frames, cranks, handlebars, seat posts, brake levers, stems, bottle cages. Practically everything.

I understand why they’re doing this: carbon fiber is light, it’s strong, and it can be made into practically any shape. Fine, I get that.

But what the heck is carbon fiber? I mean, I know what the two words are, kind of. “Carbon” is what pretty much everything in the universe is made of, and “fiber” is a thread of some sort or another, and if you eat enough of it, you poop on a regular basis. Excellent.

But when you put those two words together — “carbon fiber” — somehow you’ve suddenly got this outrageously strong stuff that’s really light that you can make into any shape?

It sounds like dark magick to me, Fatty.

Please help me understand what this stuff is and how it works, so I can explain it to other people without giving you credit.

Best Regards,

Duane

PS: Please also explain how CDs work.

Duane, you’ve asked an interesting question, and a timely one at that, since I am currently in the process of revising the Wikipedia entry on carbon fiber for accuracy and completeness. And also, quite frankly, for interestingness, because the current entry is so dull that I simply have not been able to bring myself to read it.

Here, in plain and understandable English, is my explanation of what carbon fiber is, how it can be shaped into practically anything, and why it is is so light and strong.

What is Carbon Fiber?

Carbon is the most plentiful element on Earth. Except hydrogen, I think. And oxygen too, maybe. And probably nitrogen, or was it helium? But after that, carbon for sure.

My point is that there’s a lot of carbon.

But what does carbon look like? Well, coal is pretty much pure carbon. So there you go. Carbon is black and flaky, and it’s pretty heavy. And if you drop it it shatters into a bunch of pieces.

“But Fatty,” I hear you say, “Heavy and rock-shaped and flaky and brittle aren’t the kind of properties I generally associate with carbon fiber bikes at all! Or at least not for the past couple years!”

And that’s because carbon is only like that (heavy, brittle, and coal-colored) before you turn it into fibers. Now a “fiber,” as you know, is really nothing more than a thread. And threads are flexible (not brittle) and light (not heavy) and don’t shatter when you drop them on the sidewalk.

So you definitely want to make your carbon fiber-y if you’re going to make a bike out of it.

To do this, you extrude coal through something that’s kind of like a pasta maker, except the pasta is really, really thin. And it’s not extruding a semolina-based dough, it’s using carbon.

And then, once you’ve put the coal through the pasta machine, you boil it for eight minutes. Any longer than that and you’ve got soggy, limp carbon fiber and no amount of pasta sauce and cheese will ever fix it. Believe me, I’ve tried.

[NOTE: Since coal is 99% pure carbon, and coal burns, and most threads burn, be aware that your carbon fiber bike is very, very flammable! And it will give off a thick black smoke when it burns, and the EPA will come and have a very stern conversation with you. Still, the knowledge that your bike burns can be useful in survival situations. But if someone dares you to jump your carbon fiber bike over a bonfire, do NOT take the dare.]

Why Is Carbon Fiber Light?

Now that you understand what carbon fiber is, your next question is, undoubtedly, “Why is it (i.e., carbon fiber, not your question) light?” The answer to this (i.e., carbon fiber, not your question) is really quite simple. Carbon fiber is light because a fiber is nothing more than a thread, and threads are light.

Here’s a way to prove this to yourself and friends.

First, pick up a thread, maybe a foot or so long. See how light it is? Put the thread on your bathroom scale. On most scales, it doesn’t even register. Pretty amazing, if you ask me.

Now, just for fun, put another thread of about the same length on the scale. See? Still doesn’t register, does it? You know why? Because fibers have no weight. Mysterious, I know, but demonstrably true.

The real question is: since fibers are weightless, how come carbon fiber bikes weigh anything at all? My personal theory is that bike manufacturing companies put ball bearings in the downtubes to add weight, putting in slightly fewer ball bearings each model year. This allows them to claim less and less weight (and hence a reason to upgrade) every year.

It’s a lousy trick.

Bicycle manufacturers of the world, I’m putting you on notice. Stop putting ball bearings in the down tubes and give us our weightless bikes now!

Why is Carbon Fiber Strong?

As you know, carbon is the primary element in diamonds, and diamonds are unbelievably strong. Here, try this. Look around you and pick up a handy diamond — the biggest one you can see. Now, try to bend it.

You can’t, can you?

Now, place it between your palms and try to crush it, like you would an orange.

Not easy, is it?

See how strong diamonds are? That’s why carbon fiber bikes are strong.

But there’s even more to why carbon fiber bikes are strong. In fact, the strength of your carbon fiber comes from a number of different factors:

- The weave of the carbon fibers. Three-strand braids are extremely strong, but are rarely used. The reason why is quite interesting. Long ago braids were almost exclusively used in factories, but since most guys cannot braid to save their lives, most of the carbon fiber braids were executed by women. A discrimination lawsuit was brought to bear by a man that felt put upon, and that was that. Now the basket pattern is used most often, although some people are working on a new “interlocking pretzel” pattern, which sounds both promising and delicious.

- The thickness of the carbon fibers. Thicker is of course stronger, and the best carbon fiber bike would be where each tube is one really thick fiber. But science doesn’t know how to do that yet, and I haven’t told them because they haven’t offered me enough money.

- The kind of glue they use to hold the fibers in place. Most manufacturers go with a kind of epoxy, which is fine. Be aware, however, that some of the cheaper manufacturers use straight-up Elmer’s school glue. The best way to tell if your carbon fiber bike is mixed with Elmer’s is to smell it. If it smells like Elmer’s, it probably is. The BEST kind of glue to use, of course, is Super Glue, because that stuff is strong. But hardly anyone ever uses this anymore — even though it’s incredibly strong — due to the fact that factory workers kept gluing their fingers together.

How Is Carbon Fiber Shaped?

The final aspect I’ll cover is how carbon fiber can be formed into practically any shape. Well, first the manufacturing plant mixes some glue up and then they slather it over a layer of the carbon fiber weave, and then they do that same thing again and again — sort of a glue-and-carbon-fiber lasagna — and somehow make it into the shape they want it to be.

Or something like that.

Honestly, I have no idea how. Maybe they pinch it into the shape they want just before the glue hardens. Or maybe it’s magic. It’s a total mystery to me.

Anyway, that’s how carbon fiber works. I’m glad I could explain it to you.

PS: CDs work by using lasers!

Comments (52)

« Previous Page — « Previous Entries Next Entries » — Next Page »