08.25.2015 | 8:33 am

A “Quick Links to Previous Installments” Note from Fatty: Here’s where you’ll find the parts to this story:

A wise man once said, “Perception is everything.”

Or was it a wise woman?

Or did s/he say, “perception is nothing.”

Let’s just agree that a wise person once said, “perception is…mumblemumble.“

My point is that what you perceive and the way things can be objectively measured, can be radically different than each other.

I have an example.

The Long Way Down

Every year since the beginning of time (or at least since I’ve started doing this race), I’ve stopped at the Columbine aid station, just for a quick drink or bite to eat.

Many years, there’s been cantaloupe, and that is the best. There is nothing in the world quite so wonderful as cantaloupe at 12,600 feet in the middle of the race.

Other years, there’s been watermelon, and that’s a close second best, wonderfulness-wise.

This year, however, I wasn’t looking for mid-race refreshment. I was looking to shave every possible second off my time. So I didn’t stop. I just went around the cones and began what has to be the cruelest, least-known joke in the Leadville 100:

The first thing you do in the big descent from Columbine Mine is…climb.

Sure, it’s just for a quarter mile, maybe less, but it still seems just a little unkind. A little unfair.

Waaaaaaaaahhhhhhh.

After that, though, it’s all downhill, for seven and a half miles. But you gotta be careful, because it’s a doubletrack-width trail, and other racers are going the other direction.

And in my case, several racers who were going slower than I was on the way up were finding the new gravity situation much more to their liking and wanted to get by me.

So, lotsa people, lotsa effort, very little oxygen. It’s amazing, really, that most of us get up and down that section of trail without hurting each other. (I’m aware of a couple people who crashed out on Columbine, but don’t really know their stories.)

I do know that I was nearly brought to tears — and I am not exaggerating here — by the fact that so many people called out “Go Fatty!” to me as I rode down. Ben. The Hammer. Dave Thompson. Lindsey.

And then I passed Ken again. This time, he didn’t heckle me, but yelled, “Good job! You’re my hero.”

The man knows how to motivate people, what kind of motivation to use, and when to use it.

I breathed a sigh of relief: passing Ken here meant that I had made it past the technical 2.5 miles of the descent.

The rest would be easy.

“I had no cramps, no cramps!” I said aloud, happy I had made it through this big climb and descent without this common problem.

Later, after the race, someone would approach me and say, “Why did you say, ‘No cramps, no cramps’ as you crossed paths with me during the race.

It would not be easy to explain.

Dizzy

Friends kept yelling my name as I worked my way down the trail. Sometimes I’d recognize them in time to yell back, but more often I wouldn’t. I’d still yell, but it would be have to be something more generic, like:

“YEEEEEHAAAWWW!”

That said, I did recognize and yell to (not necessarily in this order) Rocky (whose story I shall not recount, out of respect), Dave Houston (whose story I shall not recount, because he’s currently about 18 months late on his writeup of the trip to Italy with WBR he promised me), Cory (who was eating a slab of bacon), the other Cory (I can’t believe there were two Cory’s staying at the house I rented), the other Dave (there were a total of three Daves staying at the house I rented, but that seems less amazing than two Cory’s, somehow), and DJ (I wish I had gotten a cool nickname like “DJ,” but no; I got “Fatty.”).

All of them making their way up, all of them doing their best.

I, meanwhile, was feeling…kinda weird.

And I don’t mean “weird” as in the kind of weird I usually feel. No, this was a lightheaded, disconnected weird.

I slowed down, recognizing that if I felt this way my reflexes were probably not at their best. And then I self-assessed.

Was I lightheaded because of altitude? Maybe, but I was lower now than I had been half an hour ago, and I felt fine then.

Was I lightheaded because of lack of food? I didn’t think so. I had been absolutely fastidious about my eating regimen. If I was riding hungry, this wouldn’t be the first symptom; this would come after grumbling stomach, a drop in power, and then an inability to get food down. I had none of those symptoms.

I chose to ignore it (with the exception of being a smidgen more cautious than I already was on the descent) and hope it would go away.

This, as it turned out, was a workable solution, in my case. I was never aware of the moment when I no longer felt dizzy, but eventually — before I got to the bottom of the Columbine descent — I was not.

Still, I felt like I had been taking it slow, like I had come to an almost complete stop at the hairpin corners (which also seemed very loose and dusty that day).

I felt like, as I carefully eased my way down what was in fact the least technical descent of the day, the sub-eight dream was slipping away from me.

Admiration

Through the years, the Leadville 100 mountain bike race has grown and evolved. I have fun looking back to the early days of the race (400 riders, total, with me somewhere in the middle of the pack), but I also really love the current incarnation (1600+ riders, with me being one of the lead 100 or so).

One of the things I loved best this year was that with so many riders, so spread out, I got to witness people racing and chasing their goals, for the entirety of the descent down Columbine.

So many people, working so hard to show themselves what they can do. To test themselves. It’s inspiring.

I hit the bottom of the descent, stuck out my hand for Yuri Hauswald — DK200 winner and awesome GU guy — to give me a quick five, and charged forward.

In my mind, the rest of the race would be “easy.”

Perception and Reality

I felt like I had fouled this segment of the race up by descending so cautiously, and vowed to make time up from Twin Lakes to the Pipeline.

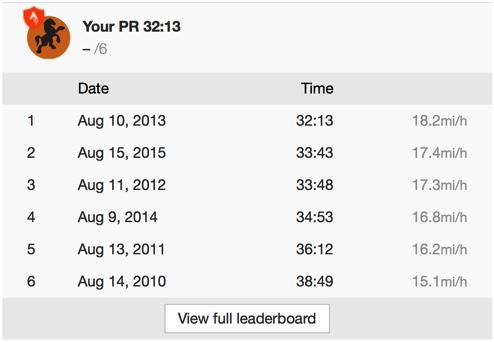

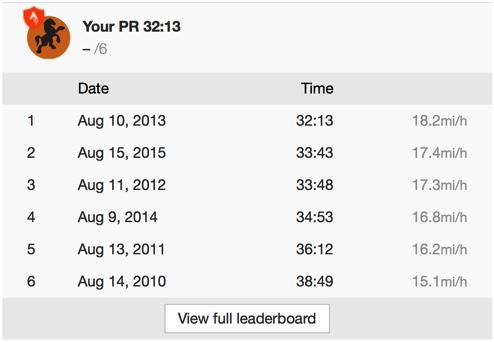

The strange thing, though, is my perception doesn’t match reality.

In truth, I had just done the descent from Columbine to Twin Lakes the second fastest I have ever done it. Just a minute and a half slower than my best, and 2.5 minutes faster than in 2011, the year I had my fastest time at Leadville.

I didn’t have the data in front of me to let me know I shouldn’t be beating myself up, though. All I had was urgency.

I needed, somehow, to step my race up.

Comments (17)

08.24.2015 | 10:29 am

A “Quick Links to Previous Installments” Note from Fatty: Here’s where you’ll find the parts to this story:

There were times, as I raced the 2015 Leadville 100, that I cursed myself and my perpetual lack of self-discipline. There were times when, as I sensed that I was not climbing as fast as I normally do, that I sarcastically said to myself, “Well, Fatty, aren’t you glad you kept postponing getting serious about your weight this year? Now that you’re working harder to go slower, was all the garbage you ate worth it?”

(I can be a little hard on myself sometimes.)

I am happy to report, however, that between the first main checkpoint in the race (Pipeline) and the second one (Twin Lakes), I did not think this kind of thought even once.

My spirits were high, my intensity was unlike anything I’ve ever felt in a race before. This may be because this part of the course is what is normally called the “flat” part of the race.

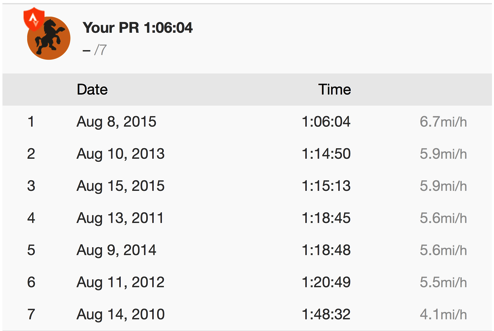

I put “flat” in sarcasm quotes because this is the elevation profile of this fifteen mile section of dirt road, pavement, doubletrack, and the course’s only singletrack:

Yeah. That’s super flat.

That said, this is the flat-est section of the course, and it clearly nets more descending than climbing (although there is still 673 feet of climbing).

And this year, while I am heavier than I would like to be, I am also stronger than I have ever been before. I can feel it. The work I did with TrainerRoad last winter did some amazing things with what I can push out of my legs. (Now I just need them to take control of my diet in a similar way.)

“I am an everlasting, hot-burning, Roman-freaking-candle,” I exulted to myself. Which made a lot more sense to me at the moment I thought it than it does now that I type it up.

My point is, I felt pretty extraordinarily powerful.

Jason — a local rider I’d been talking with about working together during this race since last April — was still with me, taking turns with me. Giving me moments of rest so I could continue pouring it on when I was up front.

“Let’s get that sub-eight!” I whooped.

“Yeah, let’s do it,” Jason agreed, though in a much more reasonable tone.

“Hey,” I asked. “Have you ever wondered why you never see snakes at this altitude?”

And then I realized: I had asked him this exact question about half an hour ago.

I resolved to stop making conversation and focus on riding.

The Quantification of Love

When you look at that elevation profile above, you can see that maintaining momentum is a huge part of racing from the Pipeline to Twin Lakes. If you can convert quick downhills into forward motion during the uphills, you can be so much faster than otherwise.

And for that reason, I was loving the Cannondale F-Si Black Inc. It tracked so beautifully on the descents, the Lefty fork soaking up rocks and bumps, with the ENVE 50-50s giving me greater confidence than I ever have had before. The Shimano XTR Di2 making it ridiculously easy for me to go to the biggest gear (just hold down the button you’ve assigned to shifting up for a couple seconds) and pedal my brains out.

Then I’d hit the corresponding uphill, keep pedaling ’til I started to bog a little, then shift one lighter, make a quick press of a button to lock out the fork, stand up and go.

The F-Si is an incredible bike.

Hey, I know I’ve shown this picture before, but I want to show it again, with the intention that this time you take a good hard look at what a beauty this bike is:

I’m not going to even try to humblebrag around it: when I do this, it is very unusual for me to not drop pretty much everyone in my zip code.

By the time Jason and I were a third of the way through this section, I noticed we had caught and re-passed most everyone who had dropped me during the Powerline descent (where my lack of skill overcame my bike’s awesomeness and I tiptoed down).

By the time we were two-thirds of the way through this section, Jason had dropped off my wheel.

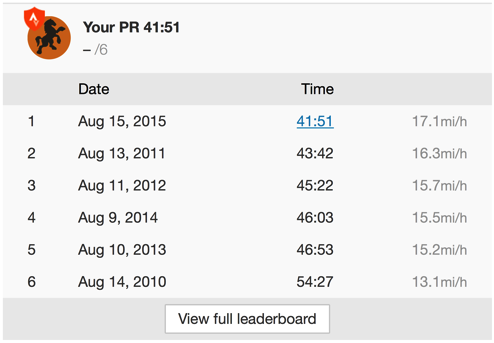

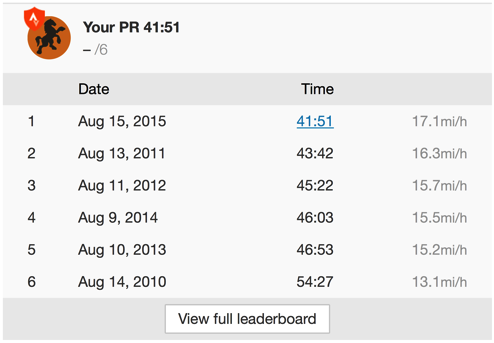

And by the time I got to where my crew had set up near the Twin Lakes timing mat, I had fully eclipsed my previous bests on this fifteen mile section:

I had just bettered my previous best (in 2011, the last time I rode a geared bike) by nearly two minutes.

Perfect Crew

I raced into the Twin Lakes Crew Corridor, looking for — and finding without difficulty — my crew: Lisa’s brother Scott and his good friend Kara.

The night before, I had written them a detailed list of what I wanted them to do at Twin Lakes 1:

- ASK if I want my arm warmers removed

- ASK if I’ve had a flat or other mechanicals

- REMOVE both bottles (note: I had finished the half-bottle of half-strength CR333 I had started the race with but had only drank half the bottle of water)

- REMOVE the empty gel packets from my center pocket

- ADD 6 new GU Roctane gels to my left pocket

- ADD a bottle of water in my front cage, a half-bottle of half-strength CR333 in my rear cage

- PLACE IN MY HANDS 4 GU Endurolyte capsules and a bottle of water to wash them down / get ahead on hydration.

Scott and Kara were amazing in executing this rather uptight list, did everything I asked in the list, and had me rolling again within fifteen seconds.

Yes, no exaggeration. Fifteen seconds. Really, someone should video how efficient they are and how amazingly straight-faced they can be about taking my ridiculous sense of urgency so seriously.

Basically, let me say this: Scott and Kara handled everything perfectly.

And now I was off to do the part of the race that looms large in most every rider’s mind: The Columbine Climb.

Fresh Vs Not-so-Fresh

One week before the Leadville 100, The Hammer and I had arrived at the base of the Columbine Mine climb (having driven straight there from Grand Junction, CO that morning), and we had attacked the Columbine Mine Climb.

Ridden just that climb, at race pace, just to see what it’s like to really go at it with fresh legs.

Here’s us at the summit, afterward:

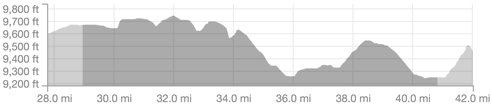

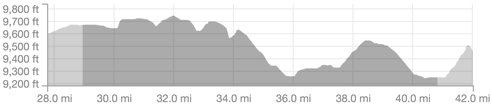

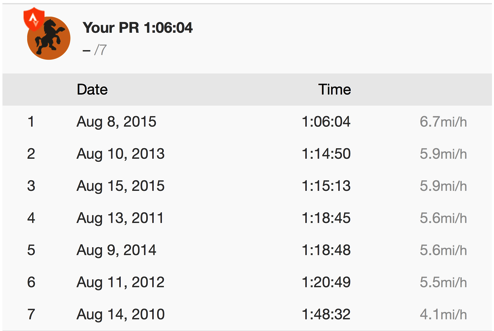

How’d I do? Well, this ought to give you an idea:

1:06:04. Which is to say, I turned in the 56th fastest time up that climb that’s ever been uploaded to Strava: one second slower than Jeff Kerkove’s best…and eleven seconds faster than Robbie Ventura’s.

And yeah, that’s nice and all (nice enough that I took the time to call it out on my blog, and you would too), but…how’d I do on race day?

Well, not bad at all…although — shockingly! — I was not as fast when riding this climb with forty miles of hard racing in my legs as I was when I was completely fresh.

1:15:13 — nine minutes more. Furthermore, it wasn’t even my fastest race-day performance. In 2013, I had done this climb in 23 fewer seconds.

Which is still not half-bad…but it was one of the parts of the race when I was giving myself a mental beatdown for not being five or seven pounds lighter.

Hi Again, Ken

As I got near the top of Columbine, nearing that 2.5-mile section where the air gets ridiculously thin and your legs suddenly have no power, I had a deja vu moment:

I saw Ken Chlouber, founder of the LT100, in the exact same place as I saw him last year.

Now, last year, this is the exchange he and I had:

With twinges of oncoming cramps in my legs, I opt to walk pretty early, and pretty often. Hey, I’ve got nothing to prove to anyone.

Except.

Except there’s a guy there. Wearing a cowboy hat. Sitting on an ATV. And he’s yelling at me.

“Get back on that bike! Get back on that bike and pedal!“

It’s Ken Chlouber, one of the founders of The Leadville 100. He’s every bit as much an icon of this race as the climbs. As much of an icon as the red carpet finish, or the big belt buckles.

And right now he’s laughing at me and telling me to get back on my bike and ride it.

I try reasoning with him.

“I’m on a singlespeed! Walking this part of the climb is a sound race strategy!”

He laughs at me again.

“Around here, we just call that being a sissy!” (Except he doesn’t exactly use the word “sissy.”)

I’ve just been called out by Ken Chlouber, as I climb the Columbine mine. It’s like being called out by Elvis as you’re passing through the doors of Graceland.

So what am I going to do?

I get back on my bike and climb. Obviously. Until I’m out of site of the man, anyway.

Remembering this, I know one thing for sure the moment I see Ken: this year he will never see me off my bike.

“Good to see you, Ken!” I shout. Because it is.

“Keep going!” he yells back. “Don’t quit!”

“I will,” I reply. “I’m having a good race!”

“Less talking, more riding!” he shouts.

I tell you. That man could be a professional heckler.

The Question

I do more of the climb on my bike than I ever have before, getting off only once, because I feel the twinges of a cramp coming on and I want to head it off.

I swallow half a dozen electrolyte capsules as I push my bike up to the end of the pitch. I’m doing an incredible job of managing my food, managing my drink, taking care of myself.

I have, it seems, become an actual expert at racing this race.

I’m getting to the top of the hard part of the Columbine climb. The last mile is easier. Almost flat, really.

I near the turnaround point. The beginning of the second half of this race.

And from many years of experience, I know: the way I ride, I can more or less count on an almost dead-even time split for my return trip. Plus or minus six minutes.

I haven’t been looking at my computer for most of the climb. It’s counterproductive: a good number might make me worry I’m going too hard; a bad number might demoralize me.

But as I reach the turnaround point, I do look down.

Four hours, and four minutes. 4:04. I’m within the margin of error for a sub-eight-hour finish at Leadville.

It’s not impossible. If I am just a tiny bit faster on the second half of the race, a 7:59:59 may just happen.

The blast of adrenaline I feel just about compensates for the near-complete lack of oxygen at 12,600 feet.

For the first time since I’ve begun doing this race, I do not stop at the Columbine aid station. I just hit the turnaround and keep going.

“Don’t you want some watermelon?” a volunteer — evidently aware of my racing tradition — calls out.

“Too fast this year!” I yell back. “No time for watermelon!”

Comments (27)

08.19.2015 | 10:49 pm

A “Quick Links to Previous Installments” Note from Fatty: Here’s where you’ll find the parts to this story:

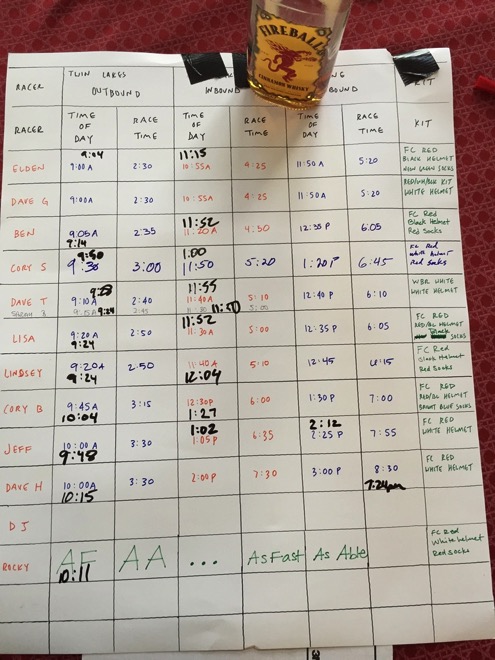

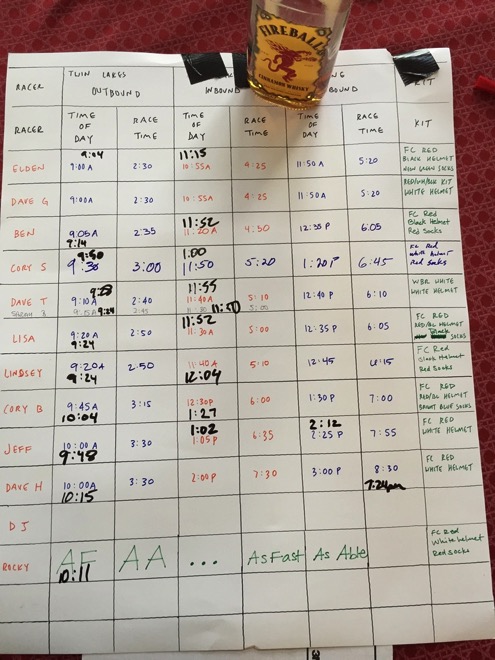

The night before the 2015 Leadville 100, Jeff Dieffenbach — my co-racer from Boggs and now an extra-good friend of Fatty — had done something wonderful. He had made a chart:

Now, try to ignore the numbers in black (the actual times) and just look at the color numbers; these are the guesstimate times everyone staying at the house we had rented, as well as how to recognize us one from another as we pulled into our community aid station / tent / hangout.

The problem for me was: I really had no idea of what kind of numbers I ought to put down. I tried figuring out aid station times that added up to under eight hours, but when I did…well, they just didn’t look realistic. I’d have to reach the turnaround at the top of Columbine in four hours, more or less.

That just sounded ridiculous. I mean, hitting the turnaround in 4:30 is a dream scenario. Half an hour faster than that? Pffff.

But I wrote those numbers down anyway. In fact, I wrote down numbers that more or less had me hitting the top of Columbine in under four hours. Because that’s a totally plausible thing that could actually happen.

And now I was racing the race. I was at the top of Powerline, one of two parts of the race I just do not enjoy.

Because I am a mediocre descender.

Let’s Get This Over With

When you are a mediocre descender on the Leadville 100 Powerline descent, you are acutely aware of four things as you descend:

- You are not going very fast

- Lots of people are passing you

- There are many bikes with flat tires on the side of the road, acting as object lessons as to what could happen if you go any faster than you are currently going

- Your hands are going numb from pulling on the brake levers nonstop since you were seven years old

Both of these happened all the time as I came down the Powerline. And also, I set a world record for “Longest Amount of Time Anyone Has Held an Expression of Shock and Dismay on One’s Face.”

Huge thanks to the amazing Linda Guerrette for this photo

Of course, I need to be honest here and say that this photo is the most humblebraggy humblebrag I’ve ever humblebragged, because while I’m self-deprecatingly poking fun at my expression, I’m really hoping that you’ll notice that for a 49-year-old, my legs do not look half bad.

In fact, my legs do not look half bad for a 25-year-old.

Furthermore, the Cannondale F-Si Black Inc I’m riding is almost without question the sexiest bike I have ever brought to a race, and it was handling better than I had any right to expect.

And also, my socks and shoes go rather fetchingly together and make me easy to distinguish from the rest of the Fatty Army on the course.

All that said, my game face still sucks pretty bad. By way of comparison, this is what it looks like when everything comes together, from legs to outfit to race face:

Kudos, by the way, to the race organizers for providing free photos to racers for download this year. That’s a nice (and unexpected) touch.

Back to the Story

Right, I was going to talk about descending the Powerline. Except I’m not really going to. Because while I was nervous the whole way down and was grateful when I reached the bottom, I raced according to my plan for this descent: treat it as one of two places in the race where time does not matter. Let people by when I could, hold my line when I needed to, and get to the bottom safe and ready to catch and slaughter those who had just passed me.

And in fact I reached the bottom safe, sound, and with legs that felt like they could and would do anything I asked of them.

Choo Choo

Powerline empties onto a few miles of pavement, followed by fifteen miles of rolling dirt road, so I knew that very soon I’d be riding hard in a paceline. So I had a gel early, had a quick drink, and then looked down the road.

There’s a guy. Riding solo. He’ll be looking to start working.

I spooled up, caught him, passed him, pointed at my back wheel, and ratcheted back my effort just a smidgen.

My train was formed.

Pulling him along, I hammered to catch another guy, then a group of two. I had built a train of five just by pulling for a couple minutes. Now it was my turn to put it to work. I pulled off left and drifted back, hoping, hoping the guys I was with knew what to do.

The guy right behind me pulled through, then drifted back immediately. Then the next guy did, and so did the next guy.

They knew. All five of us knew. I had stumbled into a Christmas Miracle of a paceline: four complete strangers who either knew how to ride a paceline or were able to quickly figure it out by example.

We flew along the pavement at a near-obscene pace, getting to the right turn in what felt like mere moments, closing in on a much larger group ahead of us.

We caught them, they joined up, and…that ruined the train. This new group hadn’t been doing a fast, efficient rotation. Who knows what they had been doing, in fact. It was no wonder our group had swept them up.

With the rotation messed up, the whole train fractured. Some racers shot ahead, others drifted back. I looked to grab a wheel of anyone who was going hard, made my choice, and joined up.

As it turns out, that was Jason. We had agreed — as far back as the True Grit Epic last spring — that we should try to work together in the Leadville 100, and now we were getting the chance.

“Let’s do this!” I whooped, feeling the intense joy of someone whose race is going impractically, impossibly well. I knew Jason’s fast. Faster than I am. Maybe this guy was going to be my ticket to a sub-eight-hour race.

We began quick rotations, which kept up for the remaining couple minutes ’til we hit the dirt.

Warrior

I’m not sure what happened after that. Maybe someone got in front of Jason, holding him up. Maybe I was just feeling too good, racing out of my head. But I lost him before we got to the first meaningful checkpoint in the race: Pipeline.

I looked at my GPS: I had done this first section in 1:56.

One hour, fifty six minutes. More or less exactly the amount of time it had taken me to get to this point in 2011, when I had finished the race in 8:18. Not exactly on track to do this race in sub-8.

Which did not even occur to me a little bit. In fact, I just thought to myself “UNDER TWO HOURS TO THE FIRST CHECKPOINT!”

In my own mind, thanks to a failure to correctly do year-to-year time comparison, I was doing awesome. Maybe Han Solo was right; sometimes it’s better to not know the odds.

I blew through the first checkpoint, howling aloud; dozens of spectators joined me in my cries.

I was in full Joyful Warrior race mode, and there was nothing I loved more than racing my bike.

Comments (20)

08.19.2015 | 7:36 am

A “Quick Links to Previous Installments” Note from Fatty: Here’s where you’ll find the parts to this story:

Five minutes before the race began, I tossed my puffy, fleecy, faux-lambswool jacket over to Katie Bolling with World Bicycle Relief. I was ready to ride, ready to race. I had not only been preparing for this race, I had been teaching clinics on how to do this race.

I was prepared.

And then, three minutes before the race began, I realized I had forgotten something: to eat.

No, I hadn’t forgotten to eat breakfast. But during the past weeks I had badgered audiences about how they need to start eating for the race before the race even begins — as they stand in the starting line. Get the first half-hour’s calories down before the race even begins.

Well, three minutes is enough time. I opened the two packets of GU Salted Watermelon Chews, chewed them down, took a slug of water, and found that this action had helped me calm down. I had gone from passively waiting for time to pass so I could start racing to actively doing something to help my race.

“Let’s do everything we can to work together, Ben,” I said.

“Sure,” Ben said, noncommittally. He’d never raced this before; he had no idea whether he’d be much faster or much slower than I am. And to be honest, I didn’t know, either.

I pivoted back and looked to Jason Sparks. I figured he and I were genuinely likely to work together. “I’ll see you on the course!”

The announcer called out the pros, gave the one minute warning, and then had the whole crowd shout out a countdown from five to the start of the race.

I pressed the start button on my Garmin 500 (yes, I’m back to the Garmin 500; I prefer it over the 510) and waited for the lag between when the shotgun announced the starting of the clock to when I would actually get to clip in and ride.

So Nice, So Easy

But here’s the thing: this time, there was hardly any lag between gun time (when the shotgun started the race) and my chip time (when I rolled over the timing mat). Maybe three or five seconds.

I was that close to the starting line, thanks to being in the silver — i.e., only the second one from the front — corral.

And I found out that the difference between starting from the front of the line of 1600 people and starting from the middle-ish part of a line of 1600-ish people is incredible.

I know, I know. It’s obvious: I expected it to be easier. Faster. Less congested.

But I had had no idea how much easier and faster and less congested it would be.

Usually, as soon as I’ve got a little bit of momentum I have to brake hard, because the 200 racers ahead of me have slowed and geared down to go up the first little rise.

But not this year. This year, the only people ahead of me were pros and might-as-well-be-pros. They didn’t slow down, so I didn’t have to shrug off speed.

Usually, there are screeching brakes all around me as I round the first right turn, after the school.

But not this year. This year racers hadn’t had time to bunch up around me yet, I had a free and clear line as I made that corner.

Usually, racers who feel their best chance for winning this race is to jockey around racers the whole way down the pavement, risking tangled handlebars every second in order to gain a tenth of a second advantage on the course.

This year, I was ahead of all that. The pros were ahead of me, the near-pros were all around me, and we were just zooming down the pavement, neat and orderly as you please.

For the first time in my Leadville 100 racing life, I didn’t heave a massive sigh of relief when I reached the bottom of this paved descent and turned onto the dirt. It had gone comfortably, perfectly, and safely.

For that moment alone, the work I had put into the Cedar City Fire Road 100 qualifying event had been worth it. And Strava bears it out: in this section, I had set a personal best, getting to the bottom of St. Kevins 1:24 faster than I had ever done so before.

That’s a lot of time to earn in the first fifteen minutes of a race.

Up St Kevins and to the Carter Summit

In real life, I am nothing if not deferential to those in a hurry. I’ll make way for people to get in front of me in traffic. I’ll open doors for people. I’ll yield my place in the grocery line? If they’re in a hurry, why not help them get where they’re in a hurry to get to?

When I’m racing, my philosophy shifts, somewhat. I become the one in the hurry, the one who wants to get around people. I’m careful to not be rude about it (at least, my race brain doesn’t perceive me as rude), but I am vocal, asking for people to move, to yield their line, to let me by.

But I didn’t have to do that at all this year.

Starting from where I had, I was already as far forward as I needed to be. I didn’t need — or even want — to get around these racers; they were working their way up the mountain as fast as I wanted to go. So I found a good wheel to follow, settled in, and rode along. No need to expend energy by moving into a bad line and accelerating past someone.

The paradox struck me: up near the front of the race, it was both easier and faster.

An Aside About Eating

I hit the sharp left turn in St Kevins in a new best time (27:31) and remembered when Reba and I had told people during our webinars: once you hit this turn, the trail continues steeply for one last short pitch, and then you’ve got a great opportunity to eat.

I took my own advice and grabbed out my first GU Roctane gel of the day. I won’t keep mentioning this, but let me say right now: I was absolutely fanatically disciplined about eating a GU Roctane gel every half hour of this race. I never made exceptions, except to perhaps sometimes eat one two or three minutes early or late based on where I was on the course.

I washed the GU down with a swig of half-strength Carborocket 333 (I’m perfectly fine with mixing nutrition brands), which is what I’d keep in one bottle the whole day; the other bottle would have water.

And for the record, I never ever ever felt any stomach discomfort, the entire day.

Folks, I have gotten the eating part of this race nailed.

Down We Go

Once you make that hard left turn at St. Kevins, you’ve really gotten the first hard climb behind you. A few more miles of rolling riding in forested doubletrack and dirt road pops you out onto the Carter’s Summit pavement, descending for three miles in about five minutes.

I marveled at how I’ve changed as a rider since 1997, when this section really scared me with how fast and steep it is. Now…I just crouched low and rode to the bottom. No drama, no sense of riding on the edge.

Part of it’s me — twentyish years of cycling experience evidently counts for something — but a lot of it is how good modern bikes are. Big wheels, low pressure tubeless tires, amazing frames and components: the cycling world has seen so much change for the good since I started this sport.

I claim credit for it all.

My top speed for the day was 41.8mph. I’m pretty sure this is where I hit it.

On To Sugarloaf

After the three miles of descending, a 1.5 mile gentle uphill gave me a chance to sit up and drink, then I was on Hagerman’s: a wide, graded (though often washboarded) slightly uphill road that gives you one of the very best places in the course to work together.

I got lucky right away: the cyclist fifty feet ahead of me looked back, saw I was near, and sat up for a moment for me to catch up.

“Let’s go get the next big group,” he said.

“For sure, for sure,” I replied.

Yes, I really said, “For sure, for sure.”

Immediately, I thought to myself, “Why did I just say, ‘For sure, for sure?’ Am I Frank Zappa? Am I singing Valley Girl? That is the dumbest thing I have ever said.”

Sometimes I can be a little self-critical.

This guy didn’t comment, however, and he was a champ at working together. Fifteen second pull, peel left, drop back and rest, repeat.

Soon we had caught…Brandon Smith, whom I honestly had not expected to see this day. Brandon had kicked my corn at Cedar City; I assumed he’d be miles ahead of me by now.

“Jump on, Banks,” I said, getting his last name wrong. Then, remembering Brandon Banks is a different local rider, I said, “Damn it. I just got your last name wrong, didn’t I?”

“Doesn’t matter,” he said, while I noted that in the past two minutes I had said two dumb things aloud and that I’d probably be best off keeping my mouth shut (figuratively, not literally, since I needed to keep my mouth wide open to get enough air) while doing this race.

We caught group after group, growing our line, ’til as we reached the sharp left turn that signaled the Sugarloaf climb, we were a dozen strong.

Which would mean nothing at all now that we were heading up one of the rockiest parts of the race. The time for pacelines was — for the time being — over.

Three Utah Boys

Brandon and I kept riding together, climbing fast and occasionally passing people.

The “occasionally” part of this disconcerted me at first. This climb is usually where I pass dozens of racers.

And then I figured it out: I wasn’t passing as many racers because this time, I was up where there weren’t a lot of racers to pass. I was already with people who are every bit as strong of climbers as I am.

I did my best to stop finding reasons to freak out over nothing.

I saw a UtahMountainBiking.com kit, knew it had to be Jason. Marveled that I was now riding with two Utah guys I know and respect as racers. That all three of us had gotten into the silver starting corral by virtue of doing well in the Fire Road 100…and that I had finished third of the three of us.

“How about that start today?” I asked? “I am never starting from the middle of the pack again.”

They agreed, briefly.

“Have you guys ever seen a snake on this course?” I then asked. “I was just thinking about how in nineteen years of doing this race, I have never seen a single snake.”

They did not reply. My ruse to get them talking had failed.

We rode in quiet, all three working hard, all three getting to the summit of Sugarloaf together.

I waved them past. “You guys know I suck at descending; I’m just going to try to survive this next part,” I said. “If I can catch you at the bottom, let’s work together on getting to Twin Lakes. Maybe the three of us can get this race done in under eight hours.”

They may have agreed; I don’t know. They just kept going, racing hard, and I was on my own for the part of the race I dread above all others: the Powerline descent.

Which seems like a good place to pick up in the next installment of this story.

Comments (13)

08.18.2015 | 7:54 am

A “Quick Links to Previous Installments” Note from Fatty: Here’s where you’ll find the parts to this story:

I was at the starting line for the 2015 Leadville 100 — my 19th start, although (with any luck) it would be my 18th finish — and I was wigging out. Wigging out more than usual, I mean.

To illustrate, I was at this moment actually at the starting line for the race for the second time. The first time, fifteen minutes ago, I had arrived with The Hammer. Then, upon arriving — and as she serenely walked toward her red corral — I abruptly turned around and rode back to our house to use the bathroom just one more time.

I was nervous. I had my reasons.

“OK, you’re standing here, now, just like you knew you’d be. And all those moments where you thought you’d lose the weight you needed to ‘later’ didn’t exactly pan out, did they?” I told myself. “You’re about seven or ten pounds heavier than you’ve been the past several years you’ve done this race. You know: about seven or ten pounds heavier than you’ve ever been since you started finishing this race under nine hours.“

And it was true. I was — am — heavier than I’d like to be, and I knew that this isn’t the kind of race where extra weight doesn’t matter.

It’s more than eleven thousand feet of climbing, after all, most of which happens at ten thousand feet and above. Sometimes way above.

“So I’m heavy,” I argued. “But I’m also really strong this year. The work I’ve done with TrainerRoad has made a big difference. I can feel it. I (spoiler alert) was the fastest I’ve ever been at The Rockwell Relay. I was (another spoiler alert) the fastest I’ve ever been at the Crusher in the Tushar. I was fast enough in the Cedar City Fire Road 100 that I got moved to this starting corrall all most all the way at the front.”

“That counts for something, right?” I asked myself.

I looked around. I was surprised how many people I knew. There was Jason, a racer I had had words with in the distant past, but now consider a friend and racing doppelgänger. And there was Brandon Smith, with whom I had shared court time.

And right next to me was my nephew-in-law, Ben Stevenson.

He and Lindsey have been doing a lot of training rides with Lisa and me. Lindsey and I have similar taste in pre-race heroic poses in big puffy coats:

Me

Lindsey

I knew that Ben was strong, and that I am generally faster than he is (sprints definitely being an exception). So why couldn’t I accept that weight notwithstanding, I had pretty goo chances at hitting my objective?

Oh, that objective. Sub-eight-hours to do Leadville. I had said it out loud. Had written it down and published it.

“You’re an idiot,” I told myself. “You didn’t get under nine hours ’til your fifteenth try, and now you think you can be nineteen minutes faster than your best? A best (8:18) which — by the way — you have not repeated in four years. When you were in your mid-forties instead of your very very very late forties.”

“But I haven’t told people about that goal in a while,” I said. “I’ll bet most people have forgotten it. Lately I’ve been saying that my objective is to beat my best time, with a stretch goal of beating Rebecca Rusch’s time in her first Leadville 100 (8:14:53). I think that might be do-able.”

Why did I want to beat Rebecca Rusch’s ’09 winning time? Because I thought it might be a useful data point to have the next time she refers to me as one of the “not so fast” people in the race.

(And also, I chose her ’09 winning time because I know there’s no way I could ever touch her ’10 – ’12 winning times.)

To be truthful, I was mentally exhausted from a jam-packed week of riding, online webinars, clinics, fundraising dinners, and preparing for the race. Somehow, I had let my taper week become incredibly busy.

Of course, we had time for a great WBR-Fatty photo shoot, courtesy of the talented Linda Guerrette:

So to be really and truly truthful, I didn’t have much to complain about. I had had a lot of fun doing these clinics and webinars; I lose count of how many times people had approached me and told me how much they had learned. And Reba really is way more than the Queen of Pain; she’s a very knowledgeable and big-hearted person.

Fatty and Reba on Columbine during pre-race clinics. Weirdest. Selfie. Ever.

And I had completed and had a celebration around my Grand Slam for Kenya, announcing — and talking on the phone with — the first winner right there in Leadville.

I tried to put all the nervousness out of my head. I failed.

Dave Wiens’ son sang the most beautiful rendition of the Star Spangled Banner I have ever heard. Honestly, he is an extraordinarily gifted singer, and the cheering after he concluded was huge.

The gun went off. It was time to put my stress and my jitters behind me.

Once again, the future had become the present.

I clipped in and took off.

Which is where we’ll pick up in the next installment.

Comments (14)

« Previous Page — « Previous Entries Next Entries » — Next Page »